The witch of Endor with a candle. Engraving by J. Kay, 1805, Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Of all the many eccentric characters who haunted the streets of my hometown in childhood, including the mentally challenged man known as Pepsi Cola and another more infamous miscreant who trafficked in underwear and firecrackers, I believe that the old crone known as Miss Capers deserves the title of the strangest Summervillian of all.[1]

In the early Sixties, my maternal grandparents stayed in a subdivided Victorian house on West 3rd Street, the upstairs having been split into two apartments, the bottom story uninhabited and warehousing a portion of some wealthy family’s estate: furniture, rugs, an extensive library with hundreds of books.[2] In the side yard there was a well. You could remove the cinder block and then the plywood and peer into an abyss. I think I remember looking down at my reflection in water, but I may have gotten that idea from a Seamus Heaney poem. Behind the house was an open grassy field and a patch of woods featuring bamboo that we called “Ghost Forest.” It was a convenient neighborhood, two houses down from Timrod Library and close to the Playground via the short cut through Pike Hole.

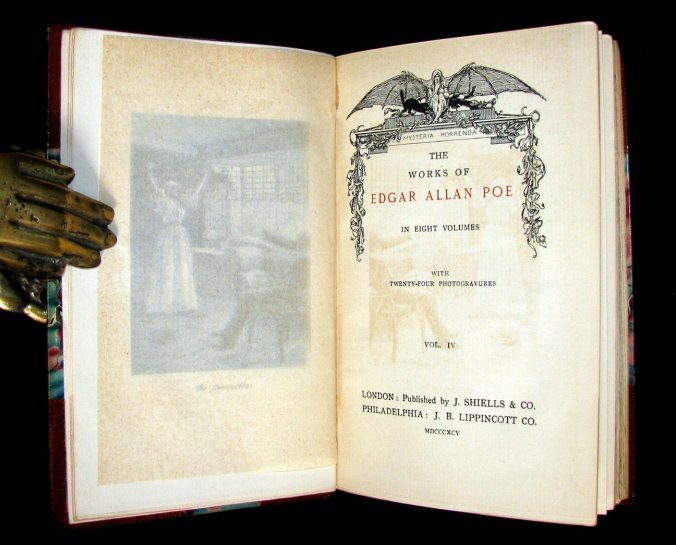

Although not an adventurous child, I somehow gained entrance into those off-limit rooms downstairs, the furniture sheeted, the air stale. I’d sneak below and explore. After repeated visitations and investigating some of the books I could reach on the lower shelves, I started secretly “borrowing” individual volumes of the Complete Works of Edgar Alan Poe.

This is from the actual set I’m talking about

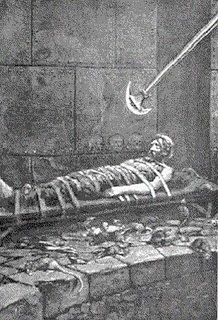

Each slender volume, bound in red, featured sheer paper sheathing occasional engravings of ravens, subterranean crypts, or rats gnawing on ropes of the dudgeon-bound protagonist of “The Pit and the Pendulum.” Into the forbidden first-story space I’d sneak, terrified I’d get caught, carefully replacing last week’s purloined octavo, flipping through other volumes, choosing another based solely on the luridness of the illustrations.

Each slender volume, bound in red, featured sheer paper sheathing occasional engravings of ravens, subterranean crypts, or rats gnawing on ropes of the dudgeon-bound protagonist of “The Pit and the Pendulum.” Into the forbidden first-story space I’d sneak, terrified I’d get caught, carefully replacing last week’s purloined octavo, flipping through other volumes, choosing another based solely on the luridness of the illustrations.

I was only eight or nine, so most of the prose lay beyond my reckoning, but I could manage lots of the poetry and some of the stories (“The Tell Tale Heart,” for example). Unable to distinguish bathos from profundity, I became completely enamored of the singsong silliness of “The Raven,” devoting several stanzas to memory. “Annabelle Lee” could bring tears to my eyes. Something sinister lay beneath those works, so the whole enterprise smacked of trafficking in pornography – though pornography would not have been in my early Sixties vocabulary.

I’d smuggle the forbidden text and read it surreptitiously in bed because I knew my parents/ grandparents wouldn’t approve of my trespassing and borrowing without asking. I liked the musty smell of the books, the way the pages whispered when I turned them, the way the illustrations lay perversely beneath diaphanous paper. Despite the buxom space sirens who cavorted on the covers of pulpy paperbacks, Sixties sci-fi couldn’t compete with the deep purple sublimations of diseased consciousness that I found in Poe.

The thing is, though, if it were the gothic that I was craving, I needed only to traipse across the hall and knock on mysterious Miss Capers’ door because she lived in the other apartment in the upstairs of my grandparents’ house. Truth is, I would not have knocked on her door for five dollars, a fortune in those days, because my brother David and I were convinced that she was a witch, and as far as diseased consciousnesses go, Miss Capers could give Bertha Mason, Mr. Rochester’s insane wife in Jane Eyre, a run for her money.

She certainly looked witchlike with her sharp nose and perpetual frown. It seemed that she only possessed two outfits, the one she wore most often a brown, probably woolen, monkish garment, the hood coming to a point pulled up over her stark white hair, even on blistering summer afternoons. Her other outfit consisted of an old-fashioned white blouse and long blue skirt. Her shoes were strange Victorian contraptions, boots, I guess you’d call them, that had several buttons on the side. She looked like she’d stepped out of the pages of a 19th Century Gothic novel.

She rarely left the house, but occasionally you’d spy her walking down the street, hunched over a cane in one hand and a bag in the other. Perpetually belligerent, she’d shake her cane at you if you passed her on the sidewalk. I seem to remember that she was terrified of thunder and lightning. One time my parents took David, my high-school aged aunt Virginia, and me into Miss Capers’ room during a storm, I think to try to comfort her, and she told me the safest thing to do during a thunderstorm was to place your face six inches from a window and to stare out at the rain. It’s the only conversation I ever had with her.

Eventually, a smell began to emanate from Miss Capers’ room, which we thought might be accumulated garbage, but when the smell metastasized into a stench, my father knocked, then pounded on the door, eventually forcing it open. I wasn’t there at the time, but what he found was Miss Capers sitting with her leg wrapped in newspapers, gangrenous, terrible to behold, literally rotting.

Of course, my parents called for an ambulance, and from what I understand, the leg was amputated, and she survived, but was taken away somewhere to live out the rest of her days and nights under some sort of supervision.

Miss Capers would have made an excellent ghost, moaning in that room whenever a thunderstorm passed, but the house has been redone, been spiffed up with all its gothic traces effaced, an incongruous setting for a specter. They should have kept that library, though. It was really something. Perhaps if I ever become a ghost, I’ll haunt it, aggrieved that the books shelves have been replaced with prissy wainscoting.

[1] According to legend, the second man would trade firecrackers to naive newcomers to town for a pair of their underwear and a photograph of them. He would say, “I’ll give you 50 pack of firecracker for your drawers.” If successful in the transaction, he would tie the underwear (always tightie whities) behind his bike, place the photograph of the victim in the underwear, and pedal his bicycle all over town. There was a local band fronted by the late Jerry Stimpson who adapted Yardbirds hit “For Your Love” into “For Your Drawers.”

Also, I realize that “crone” has fallen into disfavor because of its sexist connotations, but I use it here anyway because, well, she fit precisely the definition, especially the bad-tempered part.

[2] It’s still there, across the street from Bethany Methodist Church.

At any rate, among the rumors about Harold was that he had been on a path to becoming a physician but had some sort of mental breakdown in medical school. Whatever the case, Harold’s status in his adulthood was that of a vagrant. Riding my bicycle through the park, one time I saw him passed lying among azalea bushes with a jug next to him.

At any rate, among the rumors about Harold was that he had been on a path to becoming a physician but had some sort of mental breakdown in medical school. Whatever the case, Harold’s status in his adulthood was that of a vagrant. Riding my bicycle through the park, one time I saw him passed lying among azalea bushes with a jug next to him.