Judy Birdsong Moore

1954-2017

Because I’m used to speaking in front of crowds and have a good ear for the sound of words, over the years, several people have asked me to deliver eulogies at their loved ones’ funerals/memorial services.

When I write a eulogy, I choose a text – for my father I opted for Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” I read the poem and pegged my father as a wild man “who caught and sang the sun in flight” but who learned “too late” that he “grieved it on its way.”

I offered examples of his wildness, like the time he captured a baby alligator and kept it in our bathtub, how he performed death-defying aerobatic stunts in an open-cockpit plane he had refurbished himself. I admitted that my father really didn’t care what other people thought, that he essentially gave the finger to the world.

Nevertheless, my father could be a man of immense compassion and adhered to an unimpeachable code of personal honor. I told about the time during the height of the Civil Rights movement, much to the chagrin of our neighbors, how he invited an abused ten-year-old African American boy to come live with us until a permanent safe abode could be found for him.

What I didn’t mention was that his last words were, “Get that goddamned light out of my face.”

Instead, I ended by saying that I thought Dylan Thomas’ exhortation to “rage, rage against the dying of the light” was bad advice and quoted some scripture that had been printed on my mother-in-law’s funeral program:

Let all bitterness, and wrath, and anger, and clamor, and evil speaking be put away from you, with all malice, and be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you.

Having a text creates unity for a eulogy, helps coherence. What you want to do — or at least what I want to do – is to bring the dead back to life for a minute or two but also to help people come to terms with death’s predestined inevitability. Obviously, this last part is easier when the departed has lived a long life than it is when a life has been cut short.

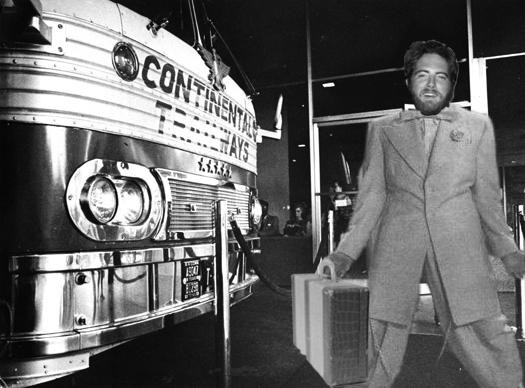

from left to right, my father, an identified woman, my mother

When it became all too obvious that my love of 40 years, Judy Birdsong, was doomed to die of lymphoma, I thought about what I might say at her memorial service, what text I might use. Although these thoughts may seem self-indulgent to some, they provided me a chance to look back over our four decades together, back over the wooing, the establishing a household, travelling the world, begetting and rearing children, the various stations in the progression of our marriage.

About a week before she died, she looked over at me and said, “You’re not planning to do a eulogy for me, are you?” She delivered this question in the tone of voice she might use if I told her I was thinking about buying a thong speedo swimsuit for Folly Beach’s New Year Day’s polar bear plunge.

“No, of course not,” I said.

So now, of course, I’m not.

However, if I were, I would make use of quotes from the many sympathy cards we’ve received. I was sort of dreading reading those cards, but it has been so comforting, so life affirming.

Here’s her college and grad school roommate Veda who can’t “think of any times we really didn’t get along or were really mad at each other” but added “I guess she really didn’t like it when I would clean her room at our apartment in Columbia, but she really never got too upset about it.” [1] It was Veda who got Judy the job at the Golden Spur. Veda adds, “Sometimes it seems I can still smell the beer from mopping the floors after closing.” It was also Veda who played matchmaker inviting me to their apartment for fried shrimp sensing Judy and I had crushes on one another but were too shy to do anything about it. What an enormous debt I owe to her.

I’ve also heard from many of Judy’s colleagues I don’t know. A principal describes her as “so pleasant to work with and so well-prepared and good with parents.”

Our niece Beth nails it when she describes Judy as “kind, generous, funny, smart, and beautiful. But I think what set her apart to me was the serenity she always possessed. In this world which is increasingly so frantic, Judy always seemed calm and peaceful, happy in her life and content in her own skin.”

Perhaps the greatest solace I have received comes from others who have lost spouses. One describes us as “travelers on the same unwished for road, members of the same broken-hearted fraternity.”

The best advice comes from fellow widower Richard O’Prey who writes

It is in that spirit that I offer you this note. I hope it lends moral support to your heroic attempt to carry on without Judy. As I did with my wife Mary, I honored her by recalling her wisdom, her counsel, her courage in supporting me during our marriage. Now I urge you to honor Judy by continuing to consult her values, her directions, her unshakable faith in you [ . . .] As you are a creature of your early youth and the effects of those who loved you, think of Judy in the same way. Think of her often and ask what you believe her advice would be under the present circumstance. Perhaps that might be the best support I can offer at this discouraging time.

Judy absolutely hated being the center-of-attention. She wouldn’t let me put in her obituary that she was named Psychology Student of the Year at PC or that her EdS thesis was published in a respected journal and has been cited in other scholarly works. In fact, she really didn’t want to have a memorial service at all but thought it was necessary because it would help others receive some closure. It was always others she was thinking of, not herself.

I’m with Richie O’Prey. Rather than seeking closure, I’ll keep Judy always nearby in my thoughts,

She’s an impossible model to live up to, she who spent the week before her death recording passwords so I could have access to her accounts. To quote Shakespeare, she died

As one that had been studied in [her] death

To throw away the dearest thing [she] owned,

As ‘twere a careless trifle.

Like I said, she’s an impossible model to live up to, but I’ll give it my best.

[1] This, by the way, gave me the false impression that Judy was a meticulous housekeeper, an illusion that quickly disappeared after I carried her over the threshold of our first apartment at 17 Limehouse Street.

Shakespeare would begin his Trump play with the inauguration speech. We’re now in Act 2, and the Comey sacking is a very important complication in the plot. Although the chaos of the firing and its aftermath is not what Aristotle called the peripetia, the turning point of a tragedy, it is the equivalent of the murder of Banquo in Macbeth, a brazen act that deepens suspicion.

Shakespeare would begin his Trump play with the inauguration speech. We’re now in Act 2, and the Comey sacking is a very important complication in the plot. Although the chaos of the firing and its aftermath is not what Aristotle called the peripetia, the turning point of a tragedy, it is the equivalent of the murder of Banquo in Macbeth, a brazen act that deepens suspicion.