Oh, I say let it rain every day. Pour. Flood the Crosstown. Swell the Edisto. Let the weeping sky paint the marsh even greener so mosquitos swarm and bats dive and devour and thrive. Out on the deck when I see their zigzagging swoops and hear the frogs croaking, I know that our habitat is healthy.

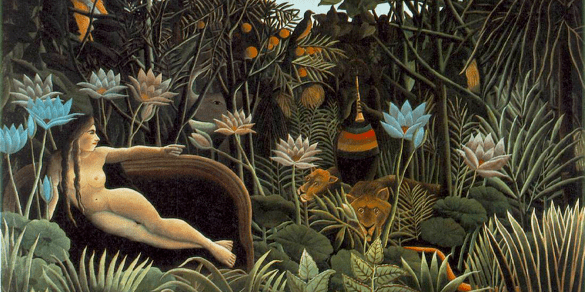

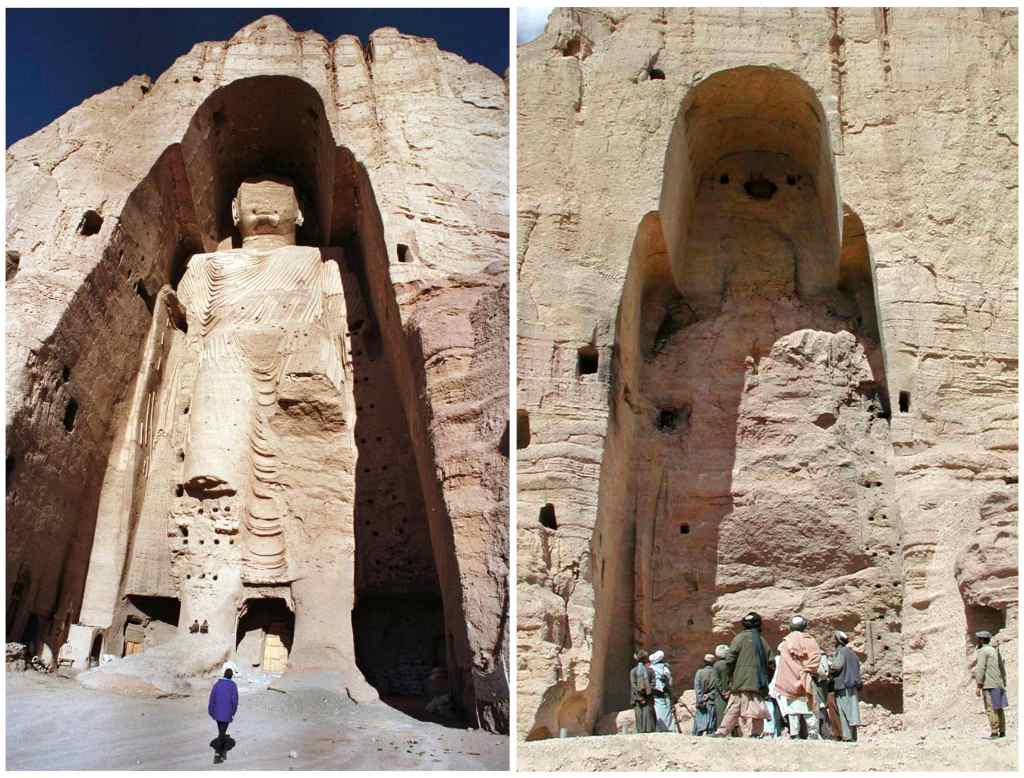

Give me a jungle any day over a desert. Jungles, which are pro-life/pro-women, give rise to animism and soulful art; deserts, on the other hand, are anti-life/anti-women, give rise to tyrannical patriarchies and edicts against pictorial art. In the jungle everything has soul; in the desert virtually nothing does.

Allow me to save a hundred or so words:

Here is Rajiv Malhotra’s take on the difference between jungle and desert cultures:

The difference in attitudes toward order and chaos is one of the chief differences discussed at length in the book [i.e., Malhotra’s Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism]. It is worth considering why the Indian religious imagination so unequivocally embraced the notion of diversity and multiplicity while others have not to a similar extent. Since all civilizations have tried to answer such existential questions as who we are, why we are here, what the nature of the Divine and the cosmos are etc., why are some Indian answers so markedly different from the Abrahamic ones?

Sri Aurobindo offers us a clue. In Dharmic traditions, unity is grounded in a sense of the Integral One, and there can be immense multiplicity without fear of “collapse into disintegration and chaos”. He suggests that the “forest” with the “richness and luxuriance of its vegetation” is both an inspiration and metaphor for India’s spiritual outlook. A quick look at world cultures and civilizations reveals how profoundly the geography and the human response to it affected those cultures. So it may well be that the physical features and characteristics of the subcontinent, once lush with tropical forests, also contributed to its deepest spiritual values (in contrast to those that were born, as the Abrahamic religions are, in the milieu of the desert).

The forest has always been a symbol of beneficence in India – a refuge from the heat, and abundant enough to support a life of contemplation without the worries of survival when worldly ties had to be severed for the pursuit of spiritual goals. (The penultimate stage of life advocated for individuals in Dharma traditions is called “vanaprastha” or “the forest stage of life”). Forests support thousands of species that survive interdependently and contain complex life and biology that changes and grows organically. Forest creatures are adaptive; they mutate and fuse into new forms easily. The forest loves to play host; newer life forms migrate to it and are rehabilitated as natives. Forests are ever evolving, their dance never final or complete.

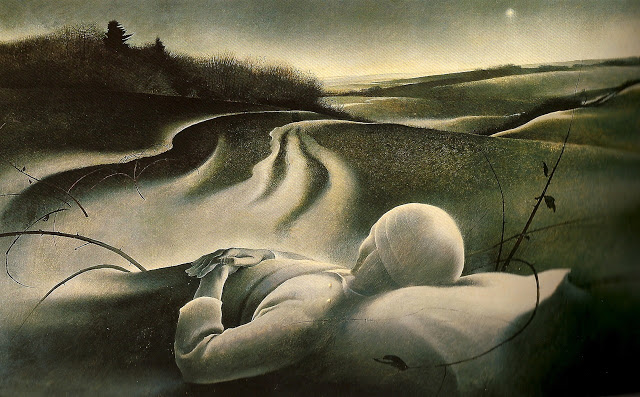

Of course, deserts can possess their own austere beauty, and given their lack of resources, human survival may well have depended on highly competitive survivalists whose creator was jealous and capable of drowning virtually all of his creation for wandering from the steep and stony way, and certainly the Hindu deity Kali isn’t exactly a benign creature herself, a destroyer extraordinaire but forgive me, I’ve wandered from my meteorological focus . . .

It isn’t raining rain you know/ It’s raining violets.