Backdrop

Sunday, I had the melancholy chore of driving from Folly Beach to Summerville to sign papers granting unsmiling folks at a funeral home permission to cremate my Aunt Virginia’s remains. It had been a strange weekend. Friday night, at the Jack of Cups Saloon, I ran into a woman just back from the emergency room after her husband had sacrificed his thumb and portions of two fingers to a buzz saw.

Jack of Cups 19 Feb 2016

He was now home zonked out on painkillers, and she was downright giddy, maybe slightly hysterical, as she showed me images of his mangled hand on her phone. Under the influence of high gravity beer, I had found the spectacle somewhat amusing in a macabre Flannery O’Connor sort of way. At the time, the incongruence of her manic good mood and the awful image of the thumb stump on the screen of her iPhone struck me as paradoxically life affirming, but 36 hours later, on this overcast Sabbath morning, the incident seemed merely strange and sad.

Adding to my melancholia is the mournful state of our body politic. The Republican Party primary in my home state and the Democratic caucuses in Nevada had just gone down. Last week, the Hoodoo household suffered a relentless barrage of robo calls that could have driven even Stewart Smiley to suicide. A recorded message from the Cruz campaign, for example, featured one of the Duck Dynasty stars shilling for Ted, quoting none other than Thomas Jefferson himself. I could hear it blaring from our landline’s speaker as I worked on Saturday’s crossword puzzle.

Because we’re smack dab in the middle of the Roman spectacle of this campaign cycle, I doubt if we can fully appreciate just how surreal it actually is. The leading Republican candidate, who has won two of the first three contests, resembles Don Rickles more than John McCain or Mitt Romney. The Republican debates seem more like Hollywood Roasts than they do serious discussions of the profound problems facing our aging Republic – the threat of ISIS, grotesque economic inequality, an epidemic of mass murders, an aging population being supported by tax dollars siphoned from the paychecks of young people with massive student loans, the increasing unrest of a black population sick and tired of the status quo – of seeing their children murdered by suspicious white neighbors or gun downed/strangled by overzealous police officers. Then there’s the matter of Flint’s water supply being poisoned by misfeasance or worse.

Speaking of race, before I left for Summerville, I had downloaded Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, a rather melancholy piece of business itself.

Because of Butterfly’ s almost universal critical acclaim[1], I had listened to snippets via iTunes but decided to not purchase the album. However, a student I’d turned onto Dr. John told me he thought I’d like the new rap music he was listening to, and the next day handed me a long handwritten list of songs, several of which were from the Lamar album.

So I decided to devote the two-hour round trip to checking out the record, listening to it once on the way to the funeral home, and once on the way back. That way I could avoid thinking about Virginia, who unlike Lamar, never made it our of her cocoon.

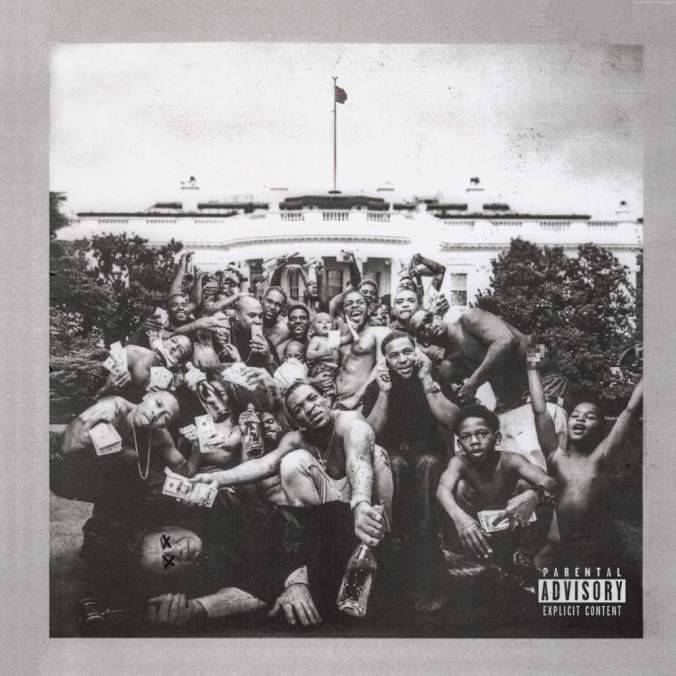

To Pimp a Butterfly

Okay, what we’re dealing with here is essentially narrative collage, a sonic novella akin to a not-all-that-positive LSD trip. Unlike most male-produced hip-hop, Butterfly doesn’t traffic in braggadocio; i.e., it is not an exercise in self-exaltation where a DJ catalogues his sexual conquests/treasure trove of top end cultural artifacts.[2] Instead, Butterfly explores Lamar’s guilt over what he sometimes perceives as the abandonment of his friends and family back in the ghetto of Compton after his entrance into the gilded realm of the rich and famous.

In a sense, it’s a classic Jungian battle between persona and self. Actually, it’s not so much like an LSD trip but more like a guided tour of someone’s unconscious with memory motifs periodically rising to the surface amid a dense swirl of background noises, bass riffs, horns, pianos, etc. Of course, the central theme is race – the difficulties urban African Americans face, shit, as Lamar would say, like teen pregnancy and gang warfare. Ultimately, the record can be seen as a parallel to the hero’s journey, a mannish boy leaves the circle of his home in the ghetto, endures a series of trials, and returns a Man with knowledge to share with his countrymen and women – in this case, his homies.

The record begins with “Wesley’s [as in Snipes] Theory,” what Greg Tate of Rolling Stone describes as “a disarming goof that’s also a lament for the starry-eyed innocence[3] lost to all winners of the game show known as Hip-Hop Idol.”

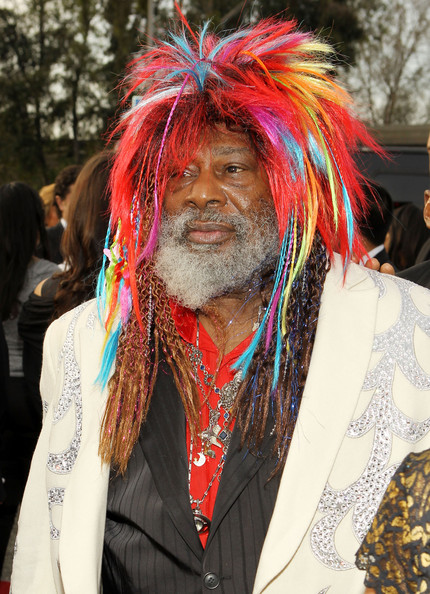

Unlike most instances of the hero’s journey, we begin in medias res, already outside the ghetto homeland and in the realm of celebrity. The track features both Dr. Dre and the great George Clinton.

Lamar describes his behavior after first getting signed to a record deal and the disillusionment that soon follows. He loses his “first girlfriend” and finds “[b]ridges burned, all across the board/Destroyed, but what for?”

He “hit[s] the dance floor,” goes predatory “snatch[ing] your little secretary bitch,” and then embarks on a spending spree with “platinum on everything.”

When I get signed homie I’mma buy a strap

Straight from the CIA, set it on my lap

Take a few M-16s to the hood

Pass ’em all out on the block, what’s good?

I’mma put the Compton swap meet by the White House

Republican, run up, get socked out

Hit the press with a Cuban link on my neck

Uneducated but I got a million dollar check, like that

Both Dr. Dre and George Clinton offer warnings. Dre’s practical:

But remember, anybody can get it

The hard part is keeping it, motherfucker

Clinton’s metaphysical:

Lookin’ down is quite a drop (It’s quite a drop, drop)

Lookin’ good when you’re on top (When you’re on top you got it)

A lot of metaphors, leavin’ miracles metaphysically in a state of euphoria

Look both ways before you cross my mind

Bad news for uneducated moguls:

Tax man comin’

Tax man comin’

Tax man comin’

Tax man comin’

Tax man comin’

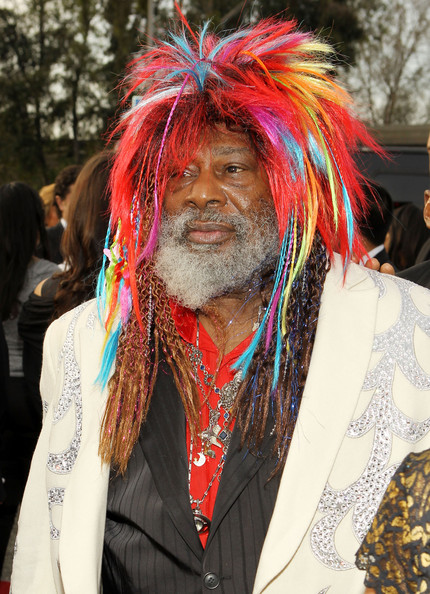

George Clinton

Musically, the next two cuts, “For Free” and “King Kunta” are my favorites, the former some serious bitchin’ rapped over a discordant, jazzy blend of drums, piano, bass, and horns. It reminds me of toned down version of Tom Waits’ “Minute,” which, in turn, reminds me of the soundtrack of a manic car chase from a ’50’s TV crime drama.

“Kin Kunta,” killer funk, owes an awful lot to James Brown’s “Payback.”

He’s mad:

Got a bone to pick

I don’t want you monkey mouth motherfuckers sittin’ in my throne again

(Aye aye nigga whats happenin’ nigga, K Dot back in the hood nigga)

I’m mad (He mad), but I ain’t stressin’

True friends, one question

Kendrick’s Mr. Big Shot:

I was contemplatin’ gettin’ on stage

Just to go back to the hood see my enemies and say

Bitch where you when I was walkin’?

Now I run the game got the whole world talkin’, King Kunta

Everybody wanna cut the legs off him, Kunta

Black man taking no losses

Bitch where you when I was walkin’?

Now I run the game, got the whole world talkin’, King Kunta

Everybody wanna cut the legs off him

This inauthenticity can’t last. Repeated throughout the narrative is a memory of a breakdown:

I remember you was conflicted

Misusing your influence

Sometimes I did the same

Abusing my power full of resentment

Resentment that turned into a deep depression

Found myself screaming in a hotel room

The 6th track corresponds to the “belly of the whale” stage of the hero’s journey, deep depression, Odysseus in the Underworld. It’s a powerful, raw, authentic confession of self-contempt.

Jonah/Kendrick

And you the reason why mama and them leavin’

No you ain’t shit, you say you love them, I know you don’t mean it

I know you’re irresponsible, selfish, in denial, can’t help it

Your trials and tribulations a burden, everyone felt it

Everyone heard it, multiple shots, corners cryin’ out

You was deserted, where was your antennas again?

Where was your presence, where was your support that you pretend?

You ain’t no brother, you ain’t no disciple, you ain’t no friend

A friend never leave Compton for profit, or leave his best friend

Little brother, you promised you’d watch him before they shot him

Where was your antennas, on the road, bottles and bitches

You faced time the one time, that’s unforgiven

You even faced time instead of a hospital visit

You should thought he would recover, well

The surgery couldn’t stop the bleeding for real

Then he died, God himself will say “you fuckin’ failed”

You ain’t try.

In the ten tracks that follow, the hero begins his ascent. God provides the Supernatural Aid universally present in the hero’s journey. The protagonist’s focus becomes less egocentric and more visionary.

On the track “i” we get apotheosis:

I done been through a whole lot

Trial, tribulations, but I know God

Satan wanna put me in a bow-tie

Praying that the holy water don’t go dry, yeah yeah

As I look around me

So many motherfuckers wanna down me

But ain’t no nigga never drown me

In front of a dirty double-mirror they found me

And I love myself

(The world is a ghetto with guns and picket signs)

I love myself

(But it can do what it want whenever it wants and I don’t mind)

I love myself

(He said I gotta get up, life is more than suicide)

I love myself

(One day at the time, sun gone shine)

Some of these latter cuts bring to mind Gil Scott Heron. The record ends with Lamar interviewing poor old dead Tupac (thanks to an old radio interview) and an oral SparkNotes-like explanation of the caterpillar/butterfly motif.

I’m, of course, not doing the record justice. I can’t come even remotely close to conveying the magical meld of sound and sense and image that is the record. Plus, I’ve left out Lucy (Lucifer) and all kinds of political subtexts, but, just leave it at this: I give it an A+++++ going on masterpiece.

Conclusion

On the morning after the Charleston massacre, I had to go to the cleaners to pick up a tux for my son’s wedding and go buy some black shoes. I reckoned I’d encounter anger among African Americans given that I was angry myself. The first black man I saw was sitting in a lawn chair drinking a beer on the edge of the parking lot of the laundry. I waved, and he waved back. A black woman rang me up at the shoe store, and when she asked me how it was going, I said that all this hatred had me feeling really low, and she said things would get better. I don’t know if she had made the connection to the shootings that had taken place about five miles away. Probably she thought it was just some kind of personal trauma, even though I was sporting all my fingers and both thumbs as I handed her the credit card.

[1] E.g., this from Rolling Stones’ Greg Tate: “To Pimp a Butterfly” is a densely packed, dizzying rush of unfiltered rage and unapologetic romanticism, true-crime confessionals, come-to-Jesus sidebars, blunted-swing sophistication, scathing self-critique and rap-quotable riot acts. Roll over Beethoven, tell Thomas Jefferson and his overseer Bull Connor the news: Kendrick Lamar and his jazzy guerrilla hands just mob-deeped the new Jim Crow, then stomped a mud hole out that ass.”

[2] He does, however, by my count twice boast of the size of his dick, claiming nine inches at one point.

[3] “Starry-eyed innocence in Compton?