He’s in the jailhouse now

He’s in the jailhouse now

Well I told him once or twice

To stop playin’ cards and a-shootin’ dice

Jimmie Rodgers

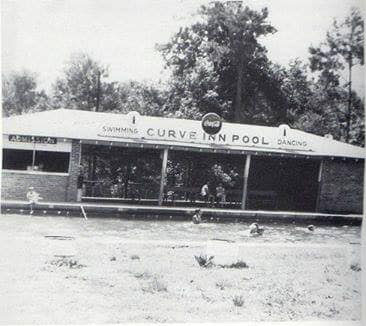

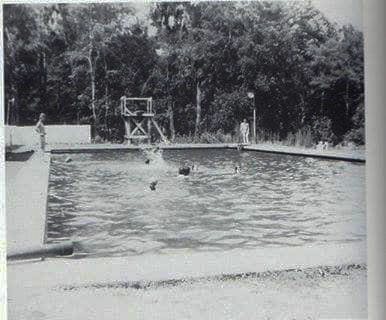

Well, given that I’ve waxed nostalgic about Summerville’s azaleas, the Curve Inn Pool, our village idiots, and county hospital, I think it’s high time I turned my misty memories to a local institution you may not have visited – the Summerville Jail.

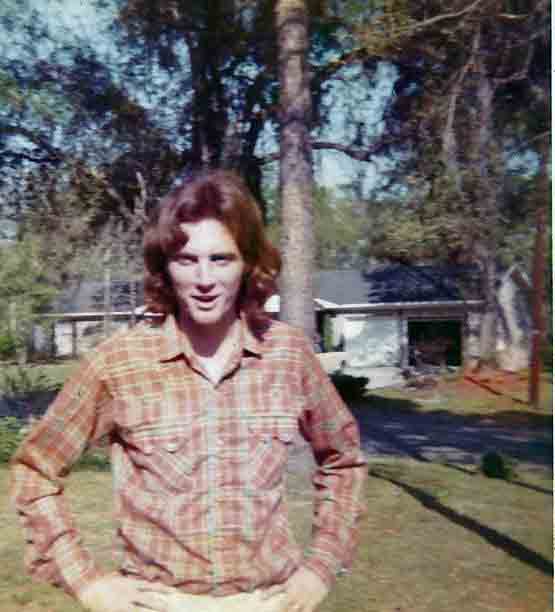

I spent one memorable night there in the summer of 1972, the summer before my junior year of college, after a group of friends and I engaged in a series of what educators nowadays call “bad decisions.” We’d smoked a joint (mostly seeds and stems) on our way to downtown Charleston to patronize a basement bar called Hog Pennys. There, of course, we downed a couple of beers, no doubt Old Milwaukees because they offered two extra ounces. [1] On the way back home to Summerville, I suspect we did another joint. I know for sure the Kinks just released album Everybody’s in Showbiz was blasting from the speakers of the car’s cassette player.

I guess it was only eleven or so when we pulled up to our hometown poolroom. We weren’t close to drunk or even all that high. After a couple of games of nine ball, we decided to call it a night.

Another friend, Keith, who hadn’t accompanied us on our journey to the peninsula, asked if he could bum a ride home, so we all piled into the car. At some point, a revolving blue light clicked on behind us. It seems the driver – I’ll call him Billy – hadn’t come to a complete stop at the most recent stop sign.

There were two different bags of cannabis, belonging to different passengers. My perhaps flawed memory has us tossing them back and forth like in that old childhood game hot potato. Someone stuffed one of the baggies beneath the front passenger’s seat. The policeman approached the driver’s side, and as the fellow riding shotgun leaned over to make sure the baggie was well hidden, the officer took note.

“What is that?” he demanded.

“Uh uh uh.”

So we were all hauled downtown to the Summerville Jail, an adjunct to the police station itself, located in those days at 225 West Luke Avenue.

The thing is that the officer did not procure the other bag, which created a very convenient out for this very inept liar. When the interrogators tried to put, as they say in crime novels, “the screws to me,” I could honestly say I didn’t know who had been in possession of the one baggie of impotent marijuana – less than a nickel’s worth – that had been confiscated.

Anyway, we were all ushered into the same cell without being fingerprinted or having mug shots taken. I recall an intercom with its red flight aglow, so we didn’t blab about what had happened. The police instructed us to call our parents, though Keith told the jailer that his mama had recently suffered a heart attack, so he’d rather spend the night in jail than wake her up with a phone call. I felt really bad for him because he was perfectly innocent.

One-by-one, my fellow inmates were released to their unhappy progenitors. When my father and mother arrived, my father was so boiling mad that I told the jailer I’d rather spend the night than be released, and he agreed that it might be a good idea.

Keith and I ended up in different cells, neither of which had bed linen, pillows, or a toilet seat, and I can’t begin to tell you how unpleasant it is waking up about 85 times in the middle of the night and remembering you’re in the clink. Morning did at last dawn, and we were served a poolroom hamburger for breakfast. My mother showed up to retrieve me; (thank goodness my father was at work). I assured Mama that the marijuana didn’t belong to me – it didn’t – but I did lie and claimed I hadn’t smoked any. Like I’ve said, I’m a terrible liar, but in this case my mother believed me.

We were supposed to be tried in St. George, and all of us but one made the trip. We sat there among other miscreants of Dorchester County on the pew-like benches of the courtroom. A self-important man with a Southern drawl called out cases and the accused stood up to acknowledge their presence . One trial involved statutory rape. Not only did they make the accused stand, but also the teenaged girl who was his victim, though she looked of age to me. Finally, the names of the last trial were called. Our names never were. Seems as if our no-show friend’s parents and procured a lawyer and had the case dropped.

Sad to say, but the last time I saw that friend was in June of 2014 at the funeral of another of that carload. Because I don’t make it to Summerville often, I don’t think I’d seen my late friend or the no show in the new century. We sat next to one another in the pew, but neither of us brought up the incident. Sadly, it had created some bad blood.

[1] 18 was the legal drinking age back in those more lenient days.

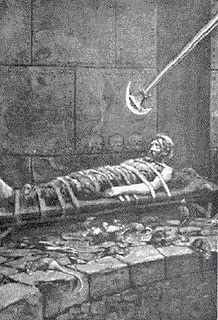

Each slender volume, bound in red, featured sheer paper sheathing occasional engravings of ravens, subterranean crypts, or rats gnawing on ropes of the dudgeon-bound protagonist of “The Pit and the Pendulum.” Into the forbidden first-story space I’d sneak, terrified I’d get caught, carefully replacing last week’s purloined octavo, flipping through other volumes, choosing another based solely on the luridness of the illustrations.

Each slender volume, bound in red, featured sheer paper sheathing occasional engravings of ravens, subterranean crypts, or rats gnawing on ropes of the dudgeon-bound protagonist of “The Pit and the Pendulum.” Into the forbidden first-story space I’d sneak, terrified I’d get caught, carefully replacing last week’s purloined octavo, flipping through other volumes, choosing another based solely on the luridness of the illustrations.

At any rate, among the rumors about Harold was that he had been on a path to becoming a physician but had some sort of mental breakdown in medical school. Whatever the case, Harold’s status in his adulthood was that of a vagrant. Riding my bicycle through the park, one time I saw him passed lying among azalea bushes with a jug next to him.

At any rate, among the rumors about Harold was that he had been on a path to becoming a physician but had some sort of mental breakdown in medical school. Whatever the case, Harold’s status in his adulthood was that of a vagrant. Riding my bicycle through the park, one time I saw him passed lying among azalea bushes with a jug next to him.