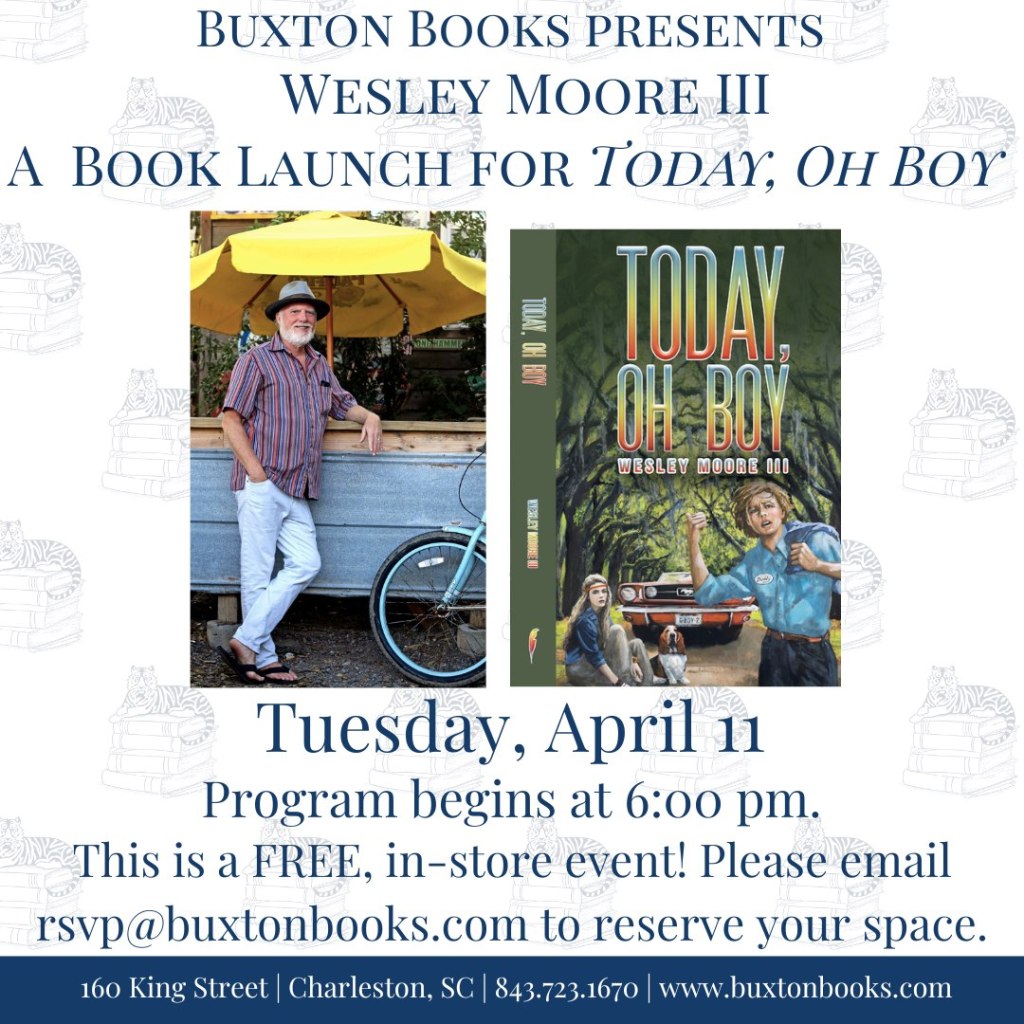

This is an excerpt from Too Much Trouble, a stand alone sequel to my novel Today, Oh Boy. In this scene, high school sweethearts Ollie Wyborn and Jill Birdsong, college freshmen home for Christmas after their first semester, meet for pool hall hotdogs in Hutchinson Square in downtown Summerville, SC. It’s the first time they’ve seen each other since their breakup in June before Ollie reported to the Air Force Academy.

Hutchinson Square

Jill’s relieved that so far her “date” with Ollie has been low-key, like two old friends catching up. He looks great. His boyish features have become more angular, his posture a bit more rigid. It’s breezy out on the square, the shadows of the trees swaying on the ground in front of their bench.

Unlike most males Jill has known, Ollie seems to genuinely care about what’s going on in her life and listens attentively. Before he left to fetch the chili dogs, he asked very thoughtful questions about life at Davidson, and his follow-up questions demonstrated sincere interest.

Now, in his absence, Jill’s mind drifts to Rusty. She wonders what he does during the day, an exile from his home.

Duh, he reads.

He’s been a booklover since she first met him in the 7th grade. In the fast-track history and English classes they shared, he was engaged, a lot more engaged than most students, and sometimes offered controversial takes on what they were reading, like calling Nick Carraway a smug, arrogant know-it-all, the worst of the slew of unlikable characters in The Great Gatsby. Then again, he didn’t seem to care all that much about his grades.

When Principal Pushcart read the daily announcements each morning over the intercom, Rusty was frequently one of the troublemakers summoned to the office. One time in the hall, Jill overheard Rusty tell Sandy Welch that he was, quote, “nothing but a crazy mixed up kid.” Jill wonders whatever became of Sandy, Tripp’s girlfriend, a wild child. Her family moved back to New Jersey not long after Tripp died, not long after the car chase she never wants to hear about again.

Here comes Ollie, smiling, walking up the paved pathway with a bag of chili dogs, fries, and a couple of Cokes.

“Is this wind bothering you?” he asks once he’s standing in front of her bench. “We could eat these somewhere else.”

“No, I like it here,” Jill says. “I like the sound the wind makes in the trees.”

He glances up at the limbs of the oak overhead, its branches swaying, its Spanish moss holding on for dear life.

“You’ll never guess who I just saw in the pool hall.”

“Who?”

“Rusty Boykin and Alex Jensen.”

“Really! Just now?”

Ollie nods. “Yep, they’re there right now.”

“Did you tell them you were with me?”

“Yeah, since girls don’t go into the poolroom, I was going to invite them over here to say hi, but they seemed to be in a very serious conversation. AJ has really put on a lot of weight, and Rusty’s hair’s down past his shoulders.”

“I know,” Jill says.

“So you’ve seen them over the holidays? Of course, Rusty works at Katz’s.”

“I saw Rusty last night.”

“Last night?”

“Yeah, we went on a date.”

“You and Rusty?”

“Yes.”

Ollie, who has been straining to be upbeat so far, frowns for the first time, then quickly recovers.

He carefully removes the white paper sleeve that holds Jill’s chili dog and hands it to her and then a small bag of rather greasy fries. She reaches down herself to grab a Coke. Ollie hands her a napkin, then retrieves his dog and fries and Coke.

“God,” Jill says, “I’d forgotten how good these are.”

God as an expletive, not gah, per usual.

“Indeed delicious. Did you have fun on your date?”

“Yes, I did. We both did.”

Ollie averts his eyes, takes a bite.

They eat in silence, the wind in the trees indeed highly audible. Ollie hadn’t noticed until Jill mentioned it. It bothers him somewhat that he doesn’t pay more attention to sounds.

Jill takes the last bite of her chili dog.

“Look, Ollie, the last thing I want to do is hurt you, but I haven’t forgotten the last words you said right before you hung up the other day. I’m sorry you think you love me, but I’ve changed a lot since June. I’m not the same Jill you knew. I’ve started drinking wine. I’ve quit believing in God. What you love is the idea you had of me back in high school.”

Ollie, ever quick on the take, instantaneously sees that it’s true. This Jill sitting next to him on the park bench isn’t the same Jill he took to the prom last May. Yet he’s more or less the same Ollie he was in high school. Oh, he’s better educated, in better physical shape, but his philosophical bearings haven’t wavered.

“I can see that,” he says, “but the funny thing is that I don’t think I’ve changed at all.”

“That’s because you’ve always been so mature, Ollie, and so good. I’d hate to see you change. I really would.”

Ollie doesn’t know what to say to this, so he says nothing.

She glances at her watch.

While Ollie pursues an errant napkin, she drops hers in the empty bag, crumples the bag, and deposits it in the trash can.

316 Camellia Drive

When Ollie returns home to his house in the Twin Oaks subdivision, he’s understandably downcast. Although he likes Rusty Boykin as a person and was even going to seek him out for companionship this week, he thinks Rusty’s all wrong for Jill—he’s wild, reckless, disorganized, and countercultural, which means he undoubtedly smokes cannabis and therefore breaks the law. That is, unless Rusty, too, has changed, but it certainly doesn’t look like it with his wild hair and raggedy outfit.

Ollie’s feeling the inherent sadness of the end of a relationship. He realizes that he and Jill will never be friends again in any meaningful sense. However, he also realizes—after all, some of the kids in Summerville call him Spock—that change is the one constant in life. While he’s sitting right now in the model airplane museum of his bedroom, his cells are multiplying and dividing, water is evaporating over the ocean, clouds are shifting shapes, the moon is waning. Virtually every high school romance ends like this. It’s, as his grandma would say, just part of life.

He’s chomping to get back to Colorado Springs. Summerville isn’t really his home. Here he’s a Yankee, and if he lived here for another 50 years, he’d still be a Yankee. He’s never completely understood the fixation they have with the Civil War.

A knock on the door interrupts his musings.

“Come in. Hi, Mom, what’s up?”

“You have a phone call. Cindy Cauthen would like to speak to you.”

“Cindy Cauthen. Okay, I’m coming.”