Episode 3 – Eatonton’s Rural Literary Legacy

[In episode 2, My ex-pat son Ned and I wended our way through backroads headed to Reynolds, formally known as Reynolds Plantation, just outside of Greensboro, Georgia, to reunite with his Aunt Becky at Uncle Dave].

Around four-thirty on Thursday, Ned and I arrived at Reynolds where we negotiated the security gate rigamarole. At the house, Becky and Dave greeted us warmly, plied us with drinks after our long (well, six hour) journey, and we did some catching up. It turns out that Becky and Dave had recently suffered a hair-raising flight from New Jersey to Atlanta, the inside of the plane perpetually rocked by turbulence for the entire time they were airborne. As she was exiting the plane, Becky found it especially disconcerting to see the pilot and copilot exchanging high fives. She informed Ned if she were going to visit him in Nuremberg, she was likely to take an ocean liner.

On Friday, Dave, who is overseeing the construction of one of the houses his son Scott is building in Reynolds, headed off to work, and Becky drove Ned and me to Eatonton so we could check out the Georgia Writer’s Museum, home of the Georgia Writer’s Hall of Fame.

Eatonton is a lovely, sleepy verdant town that reminds me of the Summerville of my youth. It seems like a pleasant place to retire, that is, if you’re not a Folly Beach hedonist hellbent on cha-cha-cha-ing yourself to death.

The museum itself, located in a coffeeshop, struck me as the literary equivalent of a science fair, consisted of tables lined up with poster board information. Eatonton and its environs have produced a remarkable number of noteworthy writers including Alice Walker, Jean Toomer of Harlem Renaissance fame, and Joel Chandler Harris, who adapted African folk tales in book form, creating the Uncle Remus stories. Milledgeville, the home of Flannery O’Connor, is a mere twenty miles south.

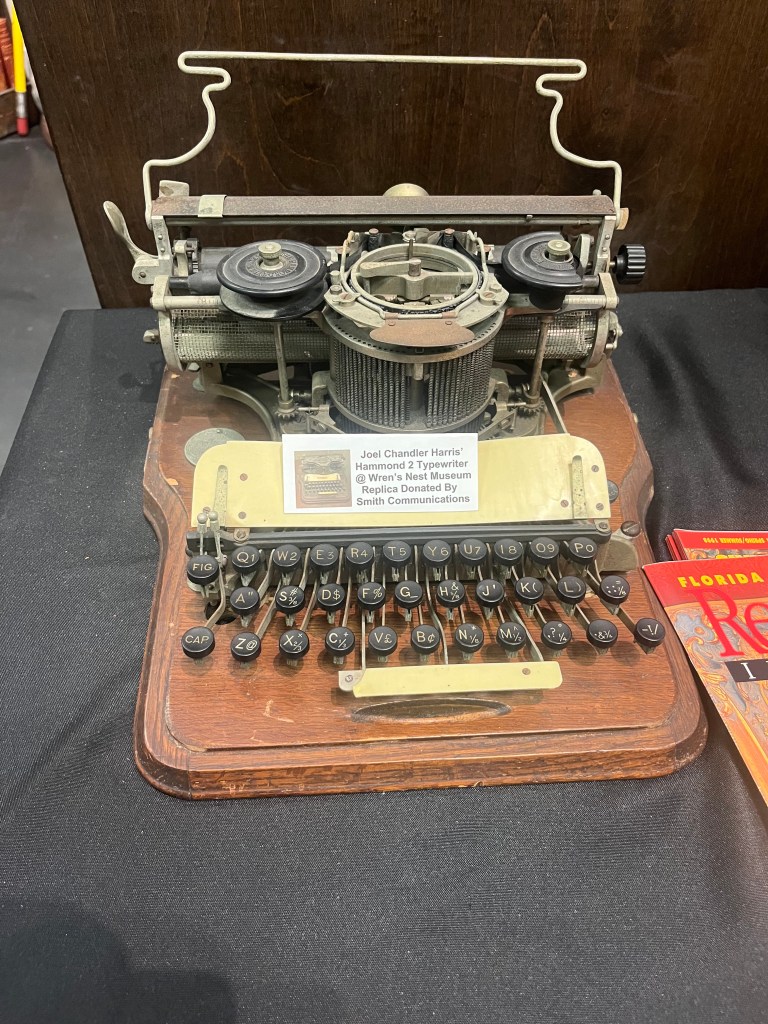

The museum houses both Joel Chandler Harris’s and Flannery O’Connor’s typewriters, plus an exhibit delineating the evolution of machines of writing, starting with primitive typewriters and ending with a progression of computers getting smaller and sleeker through the decades.

As I slowly strolled along the exhibits, The fact that Joel Chandler Harris had been born in the Barnes Inn and Tavern caught my eye. Being born in a tavern seemed odd, colorful, so I read on.

Here’s a short version of his life:

The year of his birth is uncertain, either 1845 or 1848. His mother Mary, an Irish immigrant who worked at the inn, was impregnated by a cad who abandoned his infant son and Mary. She named the baby Joel Chandler Harris after her attending physician.

Of course, illegitimacy, as it was called in my youth, was especially problematic in the antebellum South.[1] In addition to that disadvantage, Joel was redheaded and stammered, which made him a target for bullies.[2] The stigma of his “lowly” birth haunted him throughout his youth and early adulthood.

Fortunately, Dr. Andrew Reid, a prominent Eatonton physician, provided Mary and Joel with a small house behind his mansion. He also paid for Joel’s tuition (in those days public education didn’t exist in the South). Mother Mary fostered Joel’s future literary prowess by reading to him out loud, which helped him to develop the remarkable memory he would utilize in assembling the Uncle Remus tales. She read him Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield so often that he could recite lengthy passages by heart.

At fourteen, Harris dropped out of school and went to work for a newspaper, Joseph Addison Turner’s The Countrymanwith a circulation around 2,000. There Harris mastered the basics, including typesetting. Addison allowed Harris to publish his own stories and poems. Eventually, Harris moved into Turnwold Plantation, Addison’s home, located nine miles outside of Eatonton. Here Harris had access to a voluminous library and where he began devouring the classics and contemporary authors such as Dickens, Thackery, and Poe.

At Turnwold, Harris spent hundreds of hours in the slave quarters. Wikipedia claims that Harris’s “humble background as an illegitimate, red-headed son of an Irish immigrant helped foster an intimate connection with the slaves. He absorbed the stories, language, and inflections of people like Uncle George Terrell, Old Harbert, and Aunt Crissy,” who in amalgam became the narrator of the Brer Rabbit Tales, Uncle Remus.

I was unfamiliar with Harris’s biography, but what strikes me as truly remarkable is that he replicated these stories in dialect without any written sources. He essentially gave voice to and preserved these tales that had been stored in the brains of Africans, transported across the Atlantic in slave ships, and told and retold in slave cabins throughout dark nights of captivity.

Because of the Disney movie, Song of the South, Harris has been tarred (pun intended) as being a racist, which is unfortunate. What Harris did was preserve a rich trove of folklore featuring an African trickster who used his wiles to outfox foxes, tales where the underdog prevails. Of course, you can accuse Harris of cultural appropriation, but to my mind, the dialect enriches the tales, making them much more linguistically interesting.

After the war, Harris moved up in the world of journalism, working at the Atlanta Constitution for nearly a quarter century, and addition to the Remus tales, he published novels, short stories, and humorous pieces. Luminaries such as Theodore Roosevelt and Mark Twain were among his admirers. Alas, he was an alcoholic, and died from complications from cirrhosis of the liver at 59.

After our visit to the museum, Becky gave us a driving tour of the area, which includes a dilapidated chapel where Alice Walker’s ancestors are buried. We arrived back at Reynolds in the early afternoon, looking forward to Cousin Scott’s arrival the next day. At the museum, Ned had bought me Jean Toomer’s Cane, a literary mosaic of poems and short stories that brings to life a subculture, which reminds me of my work-in-progress Long Ago Last Summer, an up close and personal exploration of real life Sothern Gothic.

In short, it was a very meaningful morning and afternoon for Ned and me.

Alice Walker’s Childhood Home around 1910

[1] Of course, “bastard” was the preferred 19th Century nomenclature.

[2] As a former redhead, I can emphasize. If interested, check this LINK out.

people person. For example, although I’m a teacher, I don’t especially like young people. Don’t get me wrong — I don’t dislike children the way WC Fields disliked children; I wouldn’t conk one on the head for laughs — but I don’t like them any better than I like twenty-somethings, middle-aged people, seniors, etc. If anything, as demographics go, I like very old cognizant people the best, octogenarians and above, widows and widowers, withered folk who have seen it all, suffered irredeemable losses, but who have managed to maintain twinkles in their eyes.

people person. For example, although I’m a teacher, I don’t especially like young people. Don’t get me wrong — I don’t dislike children the way WC Fields disliked children; I wouldn’t conk one on the head for laughs — but I don’t like them any better than I like twenty-somethings, middle-aged people, seniors, etc. If anything, as demographics go, I like very old cognizant people the best, octogenarians and above, widows and widowers, withered folk who have seen it all, suffered irredeemable losses, but who have managed to maintain twinkles in their eyes.