Sleep Walking on High by Pauline Lim

I left for college as a journalism major, but I quit before ever taking even one introductory journalism class. All of the journalism professors I met at the freshman orientation were chain-smokers who seemed to have a mild case of the heebie-jeebies. Also, you had to pass a typing test, and not only didn’t I know how to type, but I also possessed –– and still do –– the fine motor skills of a platypus.[1]

So I gave up on being a newspaper scribe, and without declaring a major, took whatever classes seemed interesting –– German Expressionism in the Weimar Republic, Film Studies, Shakespeare’s comedies, etc.

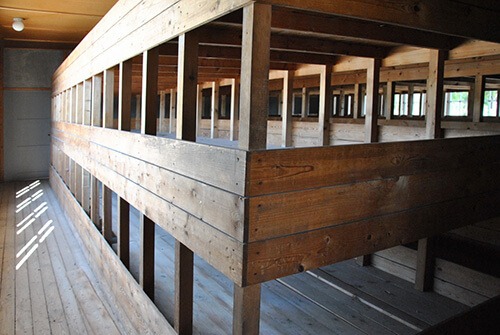

Because I was dream-ridden, impractical and enjoyed reading, when forced in my junior year to choose a major, I opted for English without giving future employment a nanosecond’s consideration. No way did I ever envision myself as a future high or middle school teacher. I recalled my highschool days, not with nostalgia, but with a feeling of good riddance, like Japanese Californians might look back on their internment during WW2.

Yet somehow I ended up teaching highschool for 34 years, and how I got that job is not unlike that Popeye cartoon where Olive Oyl sleepwalks her way across crane-hoisted girders swaying several stories above sidewalks far below during the construction of a skyscraper.

She’s unconscious but amazingly lucky as she blindly makes her way

[1] In fact, believe it or not, I’m still a hunter and pecker.

In 1977, I was engaged to be married but unemployed. I had only taken one education course as an undergraduate, so teaching high or middle school was out of the question. Not only that, but I had dropped out of graduate school after earning the requisite 30 hours.

In late August or early September of that year, I ran across an ad in the Post and Courier seeking an adjunct instructor at Trident Technical College. The ad directed the applicant contact the Dean of English, Ed Bush.

So the next day, I drove to the North Charleston campus seeking Dr. Bush, although I was supposed to apply at the central office, a detail that I had somehow overlooked. After asking around, someone directed me to Dr. Bush’s office. Obviously, I didn’t have an appointment, but there was a line outside his office, so I got in the queue and awaited my turn. When I approached his desk, he asked what class I wanted to drop or add. I informed him I was there to apply for the job advertised in the paper. After asking a few questions –– did I have a Master’s –– “no but I have the hours.”

“But you do have experience teaching, right?

“Um, yes” (after all, I had occasionally presented papers to fellow grad students in classes).

So he hired me on the spot without checking any of my credentials. After all, classes were about to begin, and they needed someone to teach English 102, Technical Report Writing, and Business Communications.

So at 24, I became a podunk adjunct professor who grew to really enjoy teaching, even continuing to teach at night when I had a full time job keeping books and training for management of a company that sold safety equipment.

Professor Rusty

My wife Judy ended up also teaching at Trident as well, but full time, and she eventually became the head of the psychology department. After being one of 12 writers selected to study under Blanche McCrary Boyd in a SC Arts Commission workshop, I quit my daytime job, wrote short fiction by day, and taught by night.[2]

However, once we had our first child, Harrison Moore, Ruler of the Third Planet, Judy wanted to be a stay-at-home mom. I took care of Harrison in the day, then drove him and handed him off to Judy before teaching my night classes. It was the worst of both worlds, sort of like being two single parents living under the same roof.

In that first autumn of being a father, I received a call from the chair of Porter-Gaud’s English Department, George Whitaker. Ed Bush, my former boss at Trident, had given George my name. Some teacher had been fired mid-year, and Porter-Gaud needed someone ASAP. I told him I couldn’t, given my child-rearing responsibilities, but that I would love to teach at Porter in the following year.

As it turned out, the fellow they hired midyear also had to be fired that spring. In addition, an older teacher, Mr. Hubbard, was retiring, and George himself was leaving to pursue writing.

So I interviewed for the job, and despite my not stellar credentials, the new chair, Sue Chanson, the greatest high school English teacher I’ve ever known, hired me, because she later told me, Ed Bush had given me such a stellar recommendation.

So perhaps there is some truth in the old adage “It’s better to be lucky than good.”

Right Olive?

[2] Other writers selected included Josephine Humphreys, Billy Baldwin, Lee Robinson, Harland Greene, Steve Hoffius, Rebecca Parke, and Greg Williams, to name a few.