In 1951 in a letter to Harold Adam Innis, Marshall McLuhan claimed that “[t]he young today cannot follow narrative, but they are alert to drama. They cannot bear description, but they love landscape and action.“ It is perhaps foolish for a pedestrian blogger to dare to contradict such a colossus as McLuhan, but I beg to differ. High school students still love to hear a story told out loud, or at least my students do.

I don’t know whether their delight in hearing oral narratives stems from nostalgia for those less complicated days of kindergarten when they sat in circles on carpeted floors, or if it stems from even more profound depths, from some deep-rooted inclination that made keen listeners around ancestral fires more likely to pick up on life-enhancing lore. Whatever the case, whenever I announce to one of my classes, “It’s story time,” they slap shut their laptops and lean towards me in eager anticipation. Of course, I don a mask, assume a postmodern irony-laden patronizing narrative voice, supply dialogue in various tonalities, and gesticulate when appropriate.

For example, last Thursday, I announced it was story time, and told them a tale which I informed them is called “Measure for Measure.”

* * *

Measure for measure by by Hannah Tompkins

Boys and girls, once upon a time in the city of Vienna, there was a Duke named Vincentio who was sort of like a Dean of Students and Principal wrapped up in one, and because Vincentio was a kindly man, he sometimes didn’t enforce the letter of the law, or even some of the laws themselves. Human nature being what it is, the citizens of Vienna started taking advantage of this laxity, the way you do by violating the dress code with your short skirts and contraband hoodies, you know, because we teachers are too lazy or pusillanimous to enforce the dress code.

Plus, some of the Vienna’s laws were ridiculously old-fashioned and inhumanely severe. For example, boys and girls, [cue Pentecostal preacher’s voice] forn-i-CA-tion was a capital crime. If an unmarried man and an unmarried woman engaged in [cue effete professorial voice] coitus and were caught, the state beheaded the man (but let the woman live much to the chagrin of some feminist critics).

But the thing is. because laws against sex were being ignored, Vienna had become – pardon the pun – a hotbed of lechery and had been overrun by strumpets (what your hiphop heroes call hos), bawds (what your hiphop heroes call pimps), and pox (what your heath teacher calls STDs).

Well, Duke Vincentio decides enough is enough, but he doesn’t want to seem like the bad guy, so he claims to be running off to Hungary and puts his Deputy Angelo in charge to do the dirty work of cleansing Vienna of riffraff and sexual escapades. Only the Duke doesn’t really leave Vienna but disguises himself as a friar so he can keep tabs on how Angelo handles things.

The Duke chose Angelo because like his name implies, he seems to be without sin. You see, this Angelo is a rule-follower extraordinaire. He would never like you, Ashley, wear a baseball cap indoors, or you, Mason, jaywalk on King Street. And not only that, not only has he never engaged in any kind of sexual activity, he has never even had the desire to. His blood, as one of the minor characters puts it, is “like snow broth.”

So Angelo gets to work pulling down bordellos (i.e. whorehouses) in the suburbs and enforcing all of the other laws pertaining to sexual misconduct.

As it turns out, the first person to get busted for intercourse is a twenty-year-old named Claudio who impregnated his finance Juliet. Even though it has been years since anyone has been arrested, much less beheaded for this crime, Angelo not only has Claudio shackled but insists he be perp-walked through the streets to advertise that the times they are a-changing.

Claudio and Juliet are a nice couple from nice familes and were engaged at the time when weak-willed they made what our guidance counsellors call “a bad decision.”

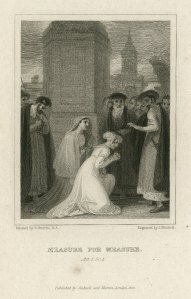

“Claudio and Isabella” by William Holman Hunt:

Everyone else in the government is sympathetic to their plight, and luckily, for Claudio, he has a beautiful and eloquent sister named Isabella who is in the process of jumping through the hoops young women jumped through in those days to become nuns. After she visits Claudio in prison, one of Claudio’s pals Luciano accompanies Isabella to Angelo’s house to have her plead for mercy. If anyone has the power to change anyone’s mind, it’s Isabella, who like I said, is not only beautiful but is so articulate that she makes your own modest storyteller sound by comparison like Lenny in Of Mice and Men.

And Isabella succeeds, all too well. Yes, she melts that snow broth of Angelo’s blood, all right, but raises its temperature so high it turns into a hot volcanic eruption of lust. That’s right, for the first time in his entire life, Angelo suffers what Patti Smith calls “the arrows of desire,” and even though Angelo knows it’s wrong, even though he fully understands the base hypocrisy of what he proposes, he tells Isabella that he will let her brother go if she will sleep with him, i.e., Angelo.

Isabella storms out in rage confident that her brother Claudio would prefer to die a thousand deaths rather than have her commit such an act of ignominy.

When she arrives at the prison to give Claudio the bad news, the Duke is there disguised as a friar trying to console Claudio with this killer contemptus mundi speech, cataloging all the slings and arrows that flesh is heir to, like growing old and ugly while your children “do curse the gout serpigo, and the rheum,/For ending thee no sooner.”

The Duke retreats and eavesdrops on Claudio and Isabella’s conversation, which goes like this.

“What’s the scoop, Isabella?”

“Good news. Lord Angelo has some business in heaven. He’s sending you there as his ambassador. You’ll be shipping off tomorrow.”

“You call that good news! That’s not good news!”

“Claudio, I hesitate to tell you this because it’s really going to infuriate you, but Angelo actually did say he’d let you go if I did something for him.”

Really! What is it? Tell me!”

“It will make you furious.”

“Why? C’mon tell me. What is it he wants you to do for him!”

“He said he’d let you go if I slept with him.”

“Really!?!?! What did you say?”

“Of course, I said what you would want me to say, of course not!”

“Wait, Isabella, you said no? Oh, sister, come on! If by committing such a sin you save a life, that sin becomes a virtue. You gotta do this for me. Dying sucks, it’s scary, please-please-please!”

Isabella’s not having any of it. She storms out furious but is approached by the Duke-in-Friar’s-Clothing who shares with her a plan.

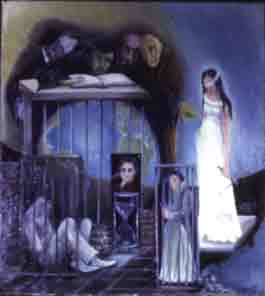

“Marianna” by Małgorzata Maj

The Friar tells Isabella that Angelo has a fiancée of his own, a woebegone woman named Mariana who pines away in a “moated grange”; that’s a “farm with a ditch around it” for you lazy students who haven’t found time yet to memorize the Oxford English Dictionary. Anyway, Angelo has refused to marry Mariana because the ship carrying her brother who was transporting riches for her dowry sank drowning her brother and losing the riches.

“No way, Jose” (or the Italian equivalent) Angelo says, “I’m not marrying you because you’re no longer rich.”

This Angelo is a piece of work, don’t you think? He makes pre-conversion Ebenezer Scrooge look charitable.

Anyway, the Duke shares the plan: “Go back and tell Angelo, yes, you’ll sleep with him, but only at this certain moated grange, and in complete silence and darkness.”

So she does so, and Angelo arrives at the moated grange, enters the bedroom, and in utter darkness does the deed with – can you guess who – that’s right, Mariana!

So Angelo returns to Vienna and demands that Claudio be put death anyway because he’s afraid Claudio will find out he’s had sex with his sister and seek revenge. He demands that Claudio’s head be brought to him for proof. What a, as Sugar-Boy says in All the King’s Men, b-b-b-b-astard!

Well, there’s another prisoner to be beheaded named Bernardine, so the Duke says behead him and bring Angelo that head, but Bernardine refuses to be put to death because he’s too hungover and is so persistent that they give up. Anyway, as luck would have it, a pirate who looks more like Claudio anyway died in prison that night, so they cut off his head and take it to Angelo.

The Friar lets Isabella think, though, that her brother is dead. It seems that friars back in those days —- remember Friar Laurence from Romeo and Juliet — had no qualms having loved ones think their kinfolk were dead.

Anyway, news arrives that the Duke is returning to Vienna. He sheds his disguise and arrives at the gates where he’s met by virtually everyone in the story who’s not in jail. Isabella tells the Duke her story, and Angelo denies it, relying on the universal common knowledge that he’s never broken a rule, much less a [no, I didn’t go there].

The Duke pretends to think that Isabella is mad because what she claims is so wildly out of whack with Angelo’s reputation. How could Angelo be, as she claims, a “virgin-violater?” But again, her speech is so articulate it seems to defy the charge of insanity.

Isabella then tells what some might call a lie, others a fib. She claims she’s slept with Angelo.

No, way, Jose (or it’s Italian equivalent) the Duke says. There’s no way Angelo would put to death a man for something he himself has done unlawfully. No one could possibly be such a vile hypocrite, much less such a noble outstanding non-jaywalking citizen like Angelo!

The Duke demands his underlings to cart Isabella to jail for lying, and she moans, “Only if the Friar were here.”

The Duke calls for the Friar, but is told by another priest that he’s sick and cannot come.

They haul Isabella off, and Marianna enters hidden by a black veil. She says Isabella was lying, that it was she — Mariana — who had slept with Angelo. She takes off her veil.

Angelo admits he used to be engaged to but has never slept with Mariana. The Duke pretends to lose patience and tells the Provost to settle matters.

The Duke splits but then reenters wearing his Friar disguise.

All the while this man named Lucio has been lying to the Duke-as-Duke telling him that the Friar had been speaking out against the Duke, calling the Duke a fishmonger [what your hiphop heroes call a pimp], etc., which of course is ironic given the Duke and Friar are one in the same. He claims the Friar has put up Mariana and Isabella to slander Angelo. A Provost tells the guards to go fetch, Isabella, which they do.

Abusing the friar, Lucio yanks off his hood to discover to his horror that – uh-oh!

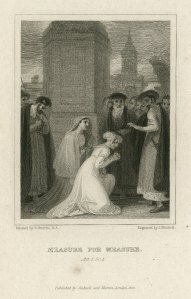

Time to wrap things up? Angelo confesses, begs to be executed, but the Duke makes him marry Mariana. Then he says the must execute Angelo because Claudio has been executed. Mariana pleads with Isabella to help save Angelo’s life, which she does on her knees in a reprise of her original pleading for Claudio’s life.

Time to wrap things up? Angelo confesses, begs to be executed, but the Duke makes him marry Mariana. Then he says the must execute Angelo because Claudio has been executed. Mariana pleads with Isabella to help save Angelo’s life, which she does on her knees in a reprise of her original pleading for Claudio’s life.

The Duke ain’t no Angelo; he pardons him, then pretends to fire the Provost who returns with — drumroll — symbol clash !!! – Claudio!!!. TA DA!

The Duke asks Isabella to marry him, but she doesn’t answer. The Duke says he’s gonna have Lucio beaten and then hanged but instead makes him marry a prostitute he had “known in the biblical sense. “ Ha Ha! Even though Lucio would rather be beaten and hanged, the Duke makes him marry anyway.

Just for a little icing, the Duke pardons Bernadine, who may be the original model for Otis Campbell in Andy of Mayberry.

So the story ends with four marriages and a pardon — though happily ever after isn’t exactly the vibe we get when the story concludes.

And that’s, boys and girls, story time for today!

* * *

Of course, this written rendition lacks the dynamics of listening to oral stories – voices, gestures, eye-contact, the dynamic energy between audience and tale-teller, questions that the students ask, etc.

I promise, though, they virtually all pay attention and often ask when are we going to have another story time.

My reason for providing them Measure for Measure’s plot is this: we’re studying that saddest of sad sacks, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, whose poem “Marianna” the students had read for homework the night before.

The epigraph of the poem, as you can see below, is “Marianna of the moated grange.” Of course, epigraphs are supposed to provide readers with a cross-reference, some insight into the meaning of the poem. After “hearing” the story of Measure for Measure what might you think the poem might be about? Justice? Hypocrisy? What Alex calls in A Clockwork Orange the “ol’ in-and-out.”

We’ll see for yourself, and if you’re not the poetry-reading type, at least check out the first and last stanzas:

Mariana

“Mariana in the Moated Grange”

(Shakespeare, Measure for Measure)

With blackest moss the flower-plots

Were thickly crusted, one and all:

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the pear to the gable-wall.

The broken sheds look’d sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch;

Weeded and worn the ancient thatch

Upon the lonely moated grange.

She only said, “My life is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

Her tears fell with the dews at even;

Her tears fell ere the dews were dried;

She could not look on the sweet heaven,

Either at morn or eventide.

After the flitting of the bats,

When thickest dark did trance the sky,

She drew her casement-curtain by,

And glanced athwart the glooming flats.

She only said, “The night is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

Upon the middle of the night,

Waking she heard the night-fowl crow:

The cock sung out an hour ere light:

From the dark fen the oxen’s low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seem’d to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the gray-eyed morn

About the lonely moated grange.

She only said, “The day is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

About a stone-cast from the wall

A sluice with blacken’d waters slept,

And o’er it many, round and small,

The cluster’d marish-mosses crept.

Hard by a poplar shook alway,

All silver-green with gnarled bark:

For leagues no other tree did mark

The level waste, the rounding gray.

She only said, “My life is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said “I am aweary, aweary

I would that I were dead!”

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up and away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

She only said, “The night is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creak’d;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek’d,

Or from the crevice peer’d about.

Old faces glimmer’d thro’ the doors

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without.

She only said, “My life is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

The sparrow’s chirrup on the roof,

The slow clock ticking, and the sound

Which to the wooing wind aloof

The poplar made, did all confound

Her sense; but most she loathed the hour

When the thick-moted sunbeam lay

Athwart the chambers, and the day

Was sloping toward his western bower.

Then said she, “I am very dreary,

He will not come,” she said;

She wept, “I am aweary, aweary,

Oh God, that I were dead!”

I declare this poem to be musically brilliant – a slow, dirge-like symphony of monotony – of fined-tuned repetitions. Of course, the danger lies in that this poem about monotony can itself become monotonous, but my students, who for the most part are conscientious, do read it, and through Socratic questioning, they ferret out imagistic patterns of dilapidation and stagnation, sonic patterns, repetitious sentence structure, etc.

But the exercise also provides another example of existentialism for them to ponder, how each individual can see the world differently. Tennyson’s melancholy cast of mind focused on the sadness of a character who engages in a bed-trick to entrap her fiancé. You have to wonder if Tennyson ever even smiled while reading the play.

In other words, for Tennyson Measure for Measure is not a comedy but a tragedy, which it very well could be if not for the contrived ending. Let’s face it, the first four acts of Romeo and Juliet with its rhyming and comical Nurse seems less like a tragedy than a comedy.

Anyway, like Hamlet says, “Nothing is neither good nor bad but thinking makes it so. Or funny or not. Or as Robert Walpole said, “Life is a comedy for those who think, a tragedy for those who feel.”

Adieu.

Although I didn’t know Pat Conroy well at all – maybe five close encounters (including one at our house on Folly Beach) – I was, however, privy to his condition during his last days because while Pat received treatment at MUSC, I met his daughters Megan and Jessica Sunday night for a drink downtown, and they ended up staying with us Monday night at the beach before heading back to Beaufort on Tuesday where Pat passed away.

Although I didn’t know Pat Conroy well at all – maybe five close encounters (including one at our house on Folly Beach) – I was, however, privy to his condition during his last days because while Pat received treatment at MUSC, I met his daughters Megan and Jessica Sunday night for a drink downtown, and they ended up staying with us Monday night at the beach before heading back to Beaufort on Tuesday where Pat passed away.