Background

One question teachers abhor is “Did I miss anything in class yesterday?”

Seniors, what follows is what you missed in class Tuesday. Teachers, if you’re looking for a lesson plan in teaching Jungian literary criticism, scroll down to “More Background.”

Although I don’t consider Jung’s theory of the Collective Unconscious scientifically valid, I do think it offers a compelling example of how humans tend to project their biology onto Nature/the Cosmos in the conjuration/production of myth/scientific theory.

To oversimplify, Jung believed that each human inherits through her genes a vast network of unconscious latent symbols – what he called archetypes – and that this inherited, universal set of unconscious preconceptions answers the question: Why do religions and myths parallel one another? These preconceptions take root and bloom in the context of various climates but maintain many similar, basic characteristics despite being products of unique cultures.

According to Jung, both Taos tribesmen and Tibetan monks possess the self-same archetypes – the same building blocks of mythology – and, though separated by 12,458 kilometers and profound cultural differences, both produce medicine wheels/mandalas out of sand that – well, see for yourself:

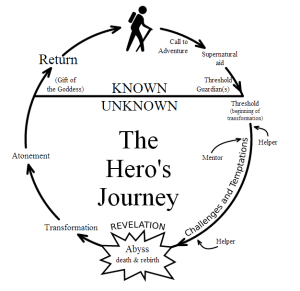

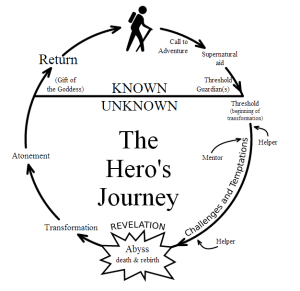

Joseph Campbell popularized this idea of the universality of mythic motifs with his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In it he charted the prototypical hero(ine)’s journey. Often, the hero is the product a miraculous birth (Moses, bulrushes) and is called upon to begin a quest (God, Moses), but sometimes he ain’t too keen on it (Moses, stuttering).

The journey starts with a Departure from the Homeland and a passage across a Mystical Threshold into a strange Other World. There the hero(ine) undergoes trials, receives supernatural aid, visits the Underworld (e.g., Hades/the belly of a whale), and finally returns with special knowledge to become Master/Mistress of Both Worlds. Variations abound, but the basic motifs are universal.

The journey starts with a Departure from the Homeland and a passage across a Mystical Threshold into a strange Other World. There the hero(ine) undergoes trials, receives supernatural aid, visits the Underworld (e.g., Hades/the belly of a whale), and finally returns with special knowledge to become Master/Mistress of Both Worlds. Variations abound, but the basic motifs are universal.

Campbell supports his universalist argument with an epic catalogue of examples from a broad range of “primitive, Oriental, and Occidental” hero myths. Once again, to oversimplify, the circular journey of the hero(ine) is in essence the journey of maturation from childhood and adolescence into adulthood — through mid-life crisis — and finally into the realm of wisdom.

In other words, the trials of the mythic hero are an outward projection of an individual’s inward journey into his unconscious where the individual unearths archetypes, brings them to the surface, and harnesses their energy.

Jung called this process of bringing archetypes to light individualization.

Individualization

If you’ve read Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, you’ve vicariously undergone individualization.

Here’s an amphetametic synopsis of Steppenwolf with Jungian archetypes in bold:

Harry Heller’s has confused his ego with his persona (public mask), which reduces him to a mere intellectual, a self-important bore who c/rudely criticizes the household art of a former colleague who has invited him to dinner. Haller attributes his gauche behavior to an inner beast, his shadow (instinctual territorial/sexual badness), which he calls the Steppenwolf. (Think Jekyll/Hyde, Bruce Banner/Incredible Hulk).

Harry Heller’s has confused his ego with his persona (public mask), which reduces him to a mere intellectual, a self-important bore who c/rudely criticizes the household art of a former colleague who has invited him to dinner. Haller attributes his gauche behavior to an inner beast, his shadow (instinctual territorial/sexual badness), which he calls the Steppenwolf. (Think Jekyll/Hyde, Bruce Banner/Incredible Hulk).

Haller’s ego has decided to cut his/its throat, but in a bar meets Hermine, his anima/doppelganger (inner female/twin), who teaches him how to dance, arranges for him to get laid, and blows his mind in a trippy Magic Theater where he discovers his two-dimensional view of himself as intellectual/wolf is over simplistic bullshit. *

Unfortunately, Haller never quite comes to understand that it’s his narcissism that makes his so wretchedly unhappy. Haller can’t, as Pablo, the Self archetype (inner Buddha/Jesus) points out, laugh at himself.

Okay, here’s how Jung claims individualization ideally works: Your ego recognizes that your public face (persona) isn’t the real you, that there’s something lurking beneath, the shadow. You tend to project your dark side, your shadow, on individuals who outwardly exhibit repressed negative aspects of your psyche that you don’t want to face (e.g., I hate the comedian Dennis Miller because he’s an arrogant, pompous, vocabulary-brandishing, ideologically opinionated asshole).

The anim/a/us* (the opposite sexed component of your psyche) plays the role of mediator by introducing your ego to its shadow. The ego knowingly incorporates the shadow’s negative but powerful instinctual wisdom into your waking consciousness, and presto, the ego has incorporated three submerged archetypes – the persona, the anima, and the shadow — into conscious recognition, which deepens and cultivates its/your humanity.

*Choosing “bullshit” instead of “hogwash” suggests I have successfully incorporated my shadow.

More Background

I teach a course called “Psychoanalytical Criticism, Modernism, and Paris in the 20’s.” Here’s what we did in class Tuesday, which I’m going to present as if it’s a lesson plan for teachers surfing the web for ideas about how to introduce students to the Jungian concepts of ego, persona, shadow, and doppelganger (mysterious twin).

Free Lesson Plan

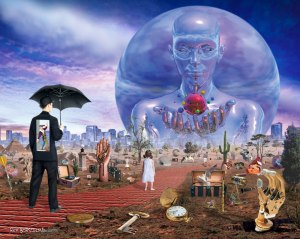

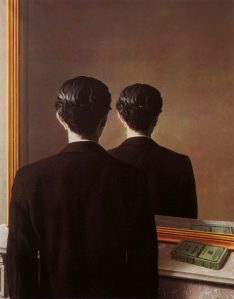

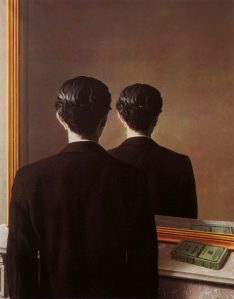

Rene Magritte : Not to be Reproduced.

This lesson occurred in an 85-minute block class, but, of course, can be divided into two or even three 40-45 minutes classes (i.e., if you incorporate the previous day’s lesson).

On the day before this lesson, Monday, I gave a lecture on the hero’s journey, socratically eliciting from students examples of heroic magical births from popular culture. E.g., Me: “You know of any heroes who had miraculous births?” Student: Yeah, Superman. Me: Explain, etc. We followed Campbell’s designated steps (see above) full circle with students citing parallel situations from other stories they’ve read.

For Tuesday’s homework, they read John Galsworthy’s “The Japanese Quince,” a freebie from the Public Domain you can download HERE.

Amphetametic synopsis of “The Japanese Quince”:

Mr. Nilson, “well known in the city,” with “firm, well-coloured cheeks” and “neat brown moustaches” and “round, well-opened, clear grey eyes” is troubled by a strange sensation in his throat and “a feeling of emptiness just under his fifth rib.”

Uncharacteristically, he walks outside to “take a turn in the Gardens” and hears a “blackbird burst into song.” The blackbird is “perched in the heart” of a tree in bloom. Mr. Nilson smiles and pauses: “the little tree was so alive and pretty! And Instead of passing on, he started there smiling at the tree.”

Feeling smug that he’s all alone there exclusively to enjoy the tree, he discovers that a “stranger” is standing next to him. He recognizes the stranger as his next-door neighbor Mr. Tandram, “well-known in the city” and who is “of about Mr. Nilson’s own height, with firm well-coloured cheeks, neat brown moustaches, and round, well-opened, clear grey eyes.” Both wear identical outfits and have newspapers clasped behind their backs.

The two engage in an awkward conversation about the tree, which they discover is a Japanese Quince because it is labeled.

It suddenly strikes Mr. Nilson that “Mr. Tandram looked a little foolish,” so he says “good morning” and retreats back into his house as does Mr. Tandram in the identical fashion.

The story ends with this sentence: “Unaccountably upset, Mr. Nilson turned abruptly into house and opened his morning paper.”

Amphetametic new critical reading of “The Japanese Quince”:

The protagonist, whose name can be transposed as “Son-of-Nothing” is a flat, static character who isn’t conscious of the story’s central conflict: that he leads a static, loveless life (note he feels an emptiness beneath his fifth rib where his heart should be).

In his adventure outside he encounters organic nature, the glories of spring, beautiful birdsong, but his encounter with his alter ego/antagonist Mr. Tandram, whose name can be transposed as “drop of boredom,” drives him back inside the sterile confines of his constricted existence.

The fact that protagonist and antagonist are both flat static characters beautifully meshes with the story’s theme of soulless materialism and the difficulty of overcoming entrenched routine.

Amphetametic Jungian reading of “The Japanese Quince”:

An ego who has confused its persona with itself is confronted by the doppleganger archetype who attempts to have the ego to see the absurdity of its persona in a mirror.. The story also can be read as a non-hero’s journey: he leaves home, crosses the threshold into a mysterious land, only to be frightened and to retreat home without having gained the secret to existence.

Before we discuss “The Japanese Quince,” I ask my students answer the following questions on paper in 100 words or fewer: Who am I? Where am I headed? Why? I assure them that I’m not going to take up their writing nor have them read their responses outloud unless they want to.

I then hand them this short piece by Borges:

Borges and I

The other one, the one called Borges, is the one things happen to. I walk through the streets of Buenos Aires and stop for a moment, perhaps mechanically now, to look at the arch of an entrance hall and the grillwork on the gate; I know of Borges from the mail and see his name on a list of professors or in a biographical dictionary. I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typography, the taste of coffee and the prose of Stevenson; he shares these preferences, but in a vain way that turns them into the attributes of an actor. It would be an exaggeration to say that ours is a hostile relationship; I live, let myself go on living, so that Borges may contrive his literature, and this literature justifies me. It is no effort for me to confess that he has achieved some valid pages, but those pages cannot save me, perhaps because what is good belongs to no one, not even to him, but rather to the language and to tradition. Besides, I am destined to perish, definitively, and only some instant of myself can survive in him. Little by little, I am giving over everything to him, though I am quite aware of his perverse custom of falsifying and magnifying things.

Spinoza knew that all things long to persist in their being; the stone eternally wants to be a stone and the tiger a tiger. I shall remain in Borges, not in myself (if it is true that I am someone), but I recognize myself less in his books than in many others or in the laborious strumming of a guitar. Years ago I tried to free myself from him and went from the mythologies of the suburbs to the games with time and infinity, but those games belong to Borges now and I shall have to imagine other things. Thus my life is a flight and I lose everything and everything belongs to oblivion, or to him.

I do not know which of us has written this page.

Obviously, once again we have here a conflict between an ego and persona. Elicit Socratic responses from the students so they understand the nature of the conflict.

We then discuss “The Japanese Quince.”

I then have them read another piece by Borges called “El Etnógrafo.” I’m indebted here to William Rowlandson’s essay ” Confronting the shadow: the hero’s journey in Borges’ ‘El Etnógrafo,'” which you can purchase for $32.95 + tax HERE. If I weren’t teaching an 85 minute class I would have assigned the story for homework.

Here it is in English:

The ethnographer

Jorge Luis Borges

Translated by Andrew Hurley

I was told about the case in Texas, but it had happened in another state. It has a single protagonist (though in every story there are thousands of protagonists, visible and invisible, alive and dead). The man’s name, I believe, was Fred Murdock. He was tall, as Americans are; his hair was neither blond nor dark, his features were sharp, and he spoke very little. There was nothing singular about him, not even that feigned singularity that young men affect. He was naturally respectful, and he distrusted neither books nor the men and women who write them. He was at that age when a man doesn’t yet know who he is, and so is ready to throw himself into whatever chance puts in his way — Persian mysticism or the unknown origins of Hungarian, the hazards of war or algebra, Puritanism or orgy. At the university, an adviser had interested him in Amerindian languages. Certain esoteric rites still survived in certain tribes out West; one of his professors, an older man, suggested that he go live on a reservation, observe the rites, and discover the secret revealed by the medicine men to the initiates. When he came back, he would have his dissertation, and the university authorities would see that it was published. Murdock leaped at the suggestion. One of his ancestors had died in the frontier wars; that bygone conflict of his race was now a link. He must have foreseen the difficulties that lay ahead for him; he would have to convince the red men to accept him as one of their own. He set out upon the long adventure. He lived for more than two years on the prairie, sometimes sheltered by adobe walls and sometimes in the open. He rose before dawn, went to bed at sundown, and came to dream in a language that was not that of his fathers. He conditioned his palate to harsh flavors, he covered himself with strange clothing, he forgot his friends and the city, he came to think in a fashion that the logic of his mind rejected. During the first few months of his new education he secretly took notes; later, he tore the notes up — perhaps to avoid drawing suspicion upon himself, perhaps because he no longer needed them. After a period of time (determined upon in advance by certain practices, both spiritual and physical), the priest instructed Murdock to start remembering his dreams, and to recount them to him at daybreak each morning. The young man found that on nights of the full moon he dreamed of buffalo. He reported these recurrent dreams to his teacher; the teacher at last revealed to him the tribe’s secret doctrine. One morning, without saying a word to anyone, Murdock left.

In the city, he was homesick for those first evenings on the prairie when, long ago, he had been homesick for the city. He made his way to his professor’s office and told him that he knew the secret, but had resolved not to reveal it.

“Are you bound by your oath?” the professor asked.

“That’s not the reason,” Murdock replied. “I learned something out there that I can’t express.”

“The English language may not be able to communicate it,” the professor suggested.

“That’s not it, sir. Now that I possess the secret, I could tell it in a hundred different and even contradictory ways. I don’t know how to tell you this, but the secret is beautiful, and science, our science, seems mere frivolity to me now.”

After a pause he added: “And anyway, the secret is not as important as the paths that led me to it. Each person has to walk those paths himself.”

The professor spoke coldly: “I will inform the committee of your decision. Are you planning to live among the Indians?”

“No,” Murdock answered. “I may not even go back to the prairie. What the men of the prairie taught me is good anywhere and for any circumstances.”

That was the essence of their conversation.

Fred married, divorced, and is now one of the librarians at Yale.

Here, as Rowlandson points out, we have the journey of the hero, Murdock, a “respectful” and trusting young man, i.e., uninitiated, who leaves his university to live with Native Americans who represent Jung’s shadow. Through his initiation Murdock learns “to dream in a language that was not that of his fathers.” As Rowlandson points out, one of Murdock’s ancestors had been killed by “Indians” who in Western culture have been traditionally denigrated as “savages.” After a series of trials, the shaman of the tribe gives Murdock “the tribe’s secret doctrine.” He then returns home an utterly changed human being.

Here, as Rowlandson points out, we have the journey of the hero, Murdock, a “respectful” and trusting young man, i.e., uninitiated, who leaves his university to live with Native Americans who represent Jung’s shadow. Through his initiation Murdock learns “to dream in a language that was not that of his fathers.” As Rowlandson points out, one of Murdock’s ancestors had been killed by “Indians” who in Western culture have been traditionally denigrated as “savages.” After a series of trials, the shaman of the tribe gives Murdock “the tribe’s secret doctrine.” He then returns home an utterly changed human being.

Note the difference from him and Mr. Nilson/Tandram

I end the class by having volunteers read their answers of who they are, where they are headed, and why.

So, yes, absentee, you did miss something Tuesday. You should borrow someone’s notes.