You know I hate, detest, and can’t bear a lie, not because I am straighter than the rest of us, but simply because it appalls me. There is a taint of death, a flavour of mortality in lies – which is exactly what I hate and detest in the world – what I want to forget. It makes me miserable and sick, like biting something rotten would do.

Charlie Marlow to his shipmates in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

No, Donald Trump isn’t a nightmare for English teachers because he uses bigly as an adverb. Nor is it that when it comes to oratory, Trump’s speeches make George W Bush seem practically Churchillian in comparison. No, the reason that Donald Trump is a nightmare for English teachers is that words to him are meaningless.

Why bother teaching someone the difference in shades of meaning between the words venial and abominable when 2 + 2 = 5?[1]

To Trump, words are just things, commodities to be manipulated for bargaining or seduction or braggadocio. We English teachers, on the other hand, tend to see words as sacred, as vessels of meaning, and we try to teach our students to choose them carefully so that their descriptions are as clear and accurate as possible, whether they are writing about their grandmothers or analyzing Lear’s betrayal by his daughters Regan and Goneril.

Of course, most if not virtually all politicians occasionally lie, but generally with subtlety and rarely when the lie can be easily refuted. This is not the case with Trump who seems to be a pathological liar. His lies are legion. He lies when it’s not necessary, seemingly for the sake of lying. To me, this lying is a very big deal, and I believe it is both my patriotic and moral duty to point out to my students why his lies are lies when they are applicable to the literature we are studying, the way I would like to think I would with Hitler’s lies if I had been teaching in Germany in the 1930’s.

Our school prayer begins with these words.

May our words be full of truth and kindness . . .

Not only are Trump’s words essentially devoid of truth and kindness, his kleptocratic tendencies as evidenced by his violation of the emolument clause, his packing the cabinet with sycophantic billionaires, and his admiration of Putin as soulmate put our very republic in danger. Nor does it help that it seems as if most Republicans in Congress don’t care about the rule of law now that one of their own can aid them in dismantling health care and cutting taxes for the 1%.

Remember Whitewater? All those Clinton investigations? Those were different people and different times.

* * *

To see what I’m getting at, allow me just one recent example of Trump’s misuse of a phrase (see italics below) and how it can distort reality to his favor.

Yesterday, on hearing that the Electoral College had made it official he would be our next president, Trump crowed, “Today marks a historic electoral landslide victory in our nation’s democracy.”

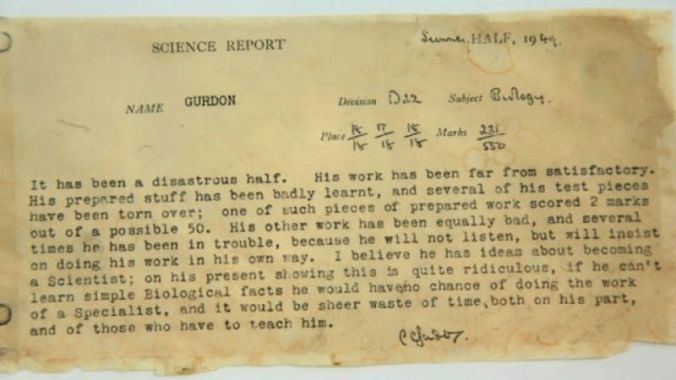

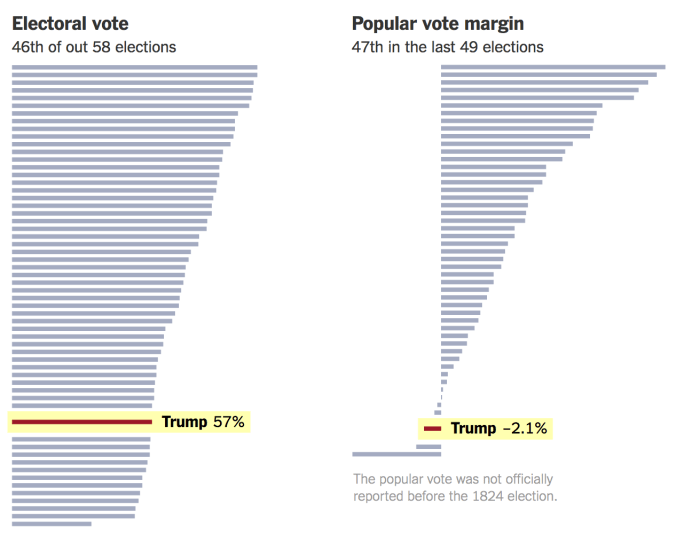

Never mind that he lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million; here’s a handy chart mapping Electoral College margins of victory from Washington to Trump:

Politfact quotes Larry Sabato, the director of the Center of Politics at the University of Virginia: “Calling a 306 electoral-vote victory a ‘landslide’ is ridiculous. Trump’s Electoral College majority is actually similar to John F. Kennedy’s 303 in 1960 and Jimmy Carter’s 297 in 1976. Has either of those victories ever been called a landslide? Of course not — and JFK and Carter actually won the popular vote narrowly.”

Of course, by declaring his historically comfortable but by no means overwhelming victory a landslide, Trump gets to have the words “historic electoral landslide” plastered in headlines and on screens across the planet. If he’s won by a landslide, the vast majority of people want whatever he wants, so that means that most people want the wealthiest Americans to receive enormous tax cuts. If this election has taught us anything, it is that a majority of voters in 30 states aren’t all that discriminating. If some hear it was a landslide on Fox News, that’s good enough for them. Here’s a quote from today’s Washington Post:

An editor at Breitbart, formerly run by senior Trump adviser Steve Bannon, said that fear [of reprisal from Trump and his minions] is well-founded [among lawmakers].

“If any politician in either party veers from what the voters clearly voted for in a landslide election … we stand at the ready to call them out on it and hold them accountable,” the person said.

In fact, if those who attend Trump rallies hear him say 2+2=5, they very well might believe him, even without having to go through the torture that O’Brian puts poor Winston Smith through in Orwell’s 1984.

How chilling to read these passages from 1984 in light of Trump’s “historic electoral landslide”:

There will be no laughter, except the laugh of triumph over a defeated enemy. There will be no art, no literature, no science. When we are omnipotent we shall have no more need of science. There will be no distinction between beauty and ugliness. There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always — do not forget this, Winston — always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — for ever.

[. . . ]

We control life, Winston, at all its levels. You are imagining that there is something called human nature which (sic) will be outraged by what we do and will turn against us. But we create human nature. Men are infinitely malleable. Or perhaps you have returned to your old idea that the proletarians or the slaves will arise and overthrow us. Put it out of your mind. They are helpless, like the animals. Humanity is the Party. The others are outside — irrelevant.’

Will I be teaching 1984 in the spring?[2] Yes. Will Trump’s name come up? You betcha! Will I be teaching “Heart of Darkness” this spring? Yes sir, of course.

[1] The latter word in this case being a much more accurate descriptor of Trump, a known swindler and self-professed sexual assaulter.

[2] By the way, click here for an extensive Pre-Trumpian lesson plans for teaching 1984.