Editor’s Note: Anthony Proveaux, a musician, photographer, and novelist based in Eugene, Oregon, has shared with me this coming-of-age essay about the social stresses of being a high school freshman in the small Southern town of Summerville, South Carolina, in a time of social upheaval. Enjoy!*

I’d suggest reading the text below the YouTube link as you listen to Anthony tell his story.

Change comes slow to small southern towns like Summerville South Carolina, where I

was born and raised. But in the late 1960s, the times they were a-changin’ fast in our little slice of Mayberry. There, like in most places across America, we sat in front of

our new color TVs and watched a world that was changing too fast for the times. The

nightly news broadcast images of unrest across the nation, followed by

stories of flower-power and love-ins, in faraway places like Haight Ashbury and not-so-far away places like Piedmont Park in Atlanta. It was hard to tell if the country was coming apart or coming together.

For young people, there was a definite sense of change in the air. Everywhere, hair was

getting longer, and music was getting louder. Down at the local Tastee-Freez, the new

sounds of Hendrix, Cream, and Creedence could be heard blasting from the 8-track

players in the muscle-cars that cruised the loop. And in school, long hair was starting

to challenge the dress-codes. Those were heady days for an impressionable young teen

like myself, and like kids everywhere, I was totally swept up in the current of events.

Of course, the elephant in America’s living room at the time, and source of much of the nation’s angst, was the very real war going on in Vietnam. Our town, like so many other places across the country, had patriotically sent their sons “over there,” but sadly, an increasing number of them weren’t coming home. But I was too young to worry about the dreaded draft notice yet, and I couldn’t make much sense of it anyway.

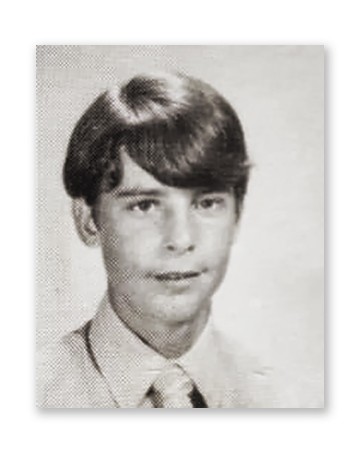

In the late 60s I was in the thick of that awkward age of early teen hood and still learning to navigate the perils of post-puberty ‘boy’s life’. Over the course of a few short years, I’d evolved from science-fair kid with a crew cut, to a mop top teen, tie-dying t-shirts on the back porch. And the most challenging part of the teenage gauntlet lay just ahead, because I was about to partake in that great social experiment called high school.

In the fall of 1969, I was a fifteen-year-old freshman at the newly opened Summerville

High. Walking those shiny hallways in the new modern buildings, passing the juniors and seniors that I had mostly only seen in my big sister’s yearbooks, was like entering a brave-new-world. It was also downright intimidating, but I was determined to fit in, and maybe even get my face above the crowd a little bit.

I’d always been a good student with good grades, but by high school my studies had

turned more towards girls, music, and teen trends (in that order). To get girls to

notice you at that age, though, you had to be more than just a bright kid. You had to

either be somebody, or be cool. Unfortunately, I was neither. Being a shy kid

from a working-class family, I was three or four rungs down on the social ladder, and

about as cool as a glass of day-old water. I definitely had some branding work to do.

So, shortly after entering the ninth grade, I began walking around Summerville High with a copy of Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test in my back pocket. Making sure the title was showing, of course. It was a book I could barely get through. The writing was way over my head, and I’d never even been properly buzzed on beer, much less done “drugs.” But the paperback sure had a cool cover, with that psychedelic sugar cube, in Peter Max wrapping paper. The K in cool really meant something back then.

That little stunt only succeeded in making me look even more nerdy than I was. I

quickly realized that if I wanted to be cool, I needed to hang out with the cool kids. In

Summerville that meant teens like the Folly Beach surfers, guys that played in bands,

and the college-bound students from the sophisticated families around town. At the new high school, I noticed that during lunch time the “in-crowd” hung out in the breezeway down by the cafeteria. So, I gradually started lurking around on the fringes of the group, half-hoping I wouldn’t be noticed, but desperately hoping that I would.

Of course, that group of cool guys and classy young ladies had no use for a gangly

ninth grader, hanging around trying to infiltrate their noontime social club. No one

was particularly rude to me. Genteel Summerville had good manners, and those with social status were always graciously “stuck-up.” So, I was politely, but pretty much totally ignored, save for a few “get lost” looks from some of the jocksters.

However, there was one dude who noticed me lurking and actually tried to bring

me into the conversation a few times. It was Rusty Moore, a quick witted

red-headed junior whom almost everyone seemed to like, except perhaps a few of the local rednecks who took his wit the wrong way on occasion.

Rusty even gave me a comeback line once. After some snobby kid cut-me-down about

this loud paisley shirt I was wearing, Rusty leaned over and whispered in my ear. “Tell him his belt looks like it’s made out of beer can pop-tops” (my antagonist was wearing one of those ‘60s belts made with metal rings). Unfortunately, I totally blew the delivery of the comeback line and just further embarrassed myself. It was a pretty pathetic stab at a touché, but I really appreciated the encouragement from Rusty.

I only lasted a week or so hanging with those hipsters. I was still a mighty-green teen, and way out of my class. And in Summerville class was still taken seriously. Our family was somewhere below the middle of the social line. So I was definitely bumping my head on the class-ceiling, trying to break into those trendy social circles.

Fortunately, cool came to our neighborhood, when a family with several rambunctious and attractive teenage daughters moved in right across the street. And as you can imagine, it wasn’t long before cool dudes were hanging around. My big sister and I soon found our own little tribe of early Summerville heads. She met a free-spirited guy, and a few years later, when I’d just turned seventeen, we followed him out to California, where we hitch-hiked, hopped trains, and bummed around for about a year. Now that was a real education. In the early 1970s, the highways were filled with on-the-road youths of every color and class, out to “Look for America.” I ended up staying on the west coast, went to college, and finally settled down in Oregon.

I never lived in Summerville again, but still have fond memories of growing up there. Navigating the perils of the teenage years and high school sticks with us all, and that early attempt at trying to climb my way up the social ladder, and falling off, always stayed with me for some reason.

During that time, I also never got to know Rusty Moore, the kid who threw me a lifeline when I tried to swim-with-the-sharks. He was a few grades above me, and I left Summerville early on. He’d certainly never remember that insignificant event anyway, but it made an impression on me. When you’re young, those little nudges along the way do make a difference. So a shout out to Rusty Moore for the nudge.

by Anthony Proveaux

*You can purchase Anthony’s historical novel Finding Charlie Patton: A Historical Novel HERE

Here’s a video modern-day Anthony (on harmonica) making music during the quarantine.

And a couple of his photographs.