Probably my favorite and most oft-repeated personal anecdote is my half-hour ride to Folly Beach chauffeured by none other than that legendary folk hero and serial killing cut-up Donald “Pee Wee Gaskins,” nee Donald Parrot, AKA Junior Parrot.[1]

In fact, the Kirkus review of my memoir Long Ago Last Summer highlights the Pee Wee incident:

One of the standout pieces involves the author hitchhiking to Folly Beach as a teenager—he and his brother survived an encounter with someone who was likely the serial killer Donald “Pee Wee” Gaskins. Even though the hitchhiking story is only four pages long, it fits a lot of frightening intrigue into a short space; the reader not only learns who Gaskins was, but gets to see the monster in action, doing things like casually burning a boy with a cigarette. [2]

Of course, during that harrowing hitch-hiking experience, Pee Wee didn’t formally introduce himself or the beer-swilling, cigarette smoking ten-year-olds accompanying him, but twenty years later when I read his autobiography Final Truth, I put two-and-two together when he mentioned that he’d take nephews on beach excursions to Folly.

By the way, the memoir also boasts an original poem entitled “Pee Wee Gaskins Stopping at a Lake House on a Summer Evening.” Because of its macabre content and abject vulgarity, I dare not post it here in its entirety, but I will share its first stanza:

Whose corpse this is I ought to know

Cause I’m the one what killed it so.

I hope no one comes by here

To watch me in the lake it throw.

So you can imagine how delighted I was last week to receive unsolicited through the mail a pre-publication copy of Dick Harpootlian’s upcoming book Dig Me a Grave: The Inside Story of the Serial Killer Who Seduced the South.

I’ve not quite finished it, but when I do, I’ll post a review here. For now, I’ll just say it’s a real page turner written in noirish prose as Harpootlian, who prosecuted Pee Wee, weaves the narrative of Pee Wee’s life with his own. Exposure to cold blooded killers transforms Harpootlian from an underground newspaper publisher[3] into a prosecutor of murderers and from an anti-capital punishment advocate into a diehard (forgive the pun) proponent.

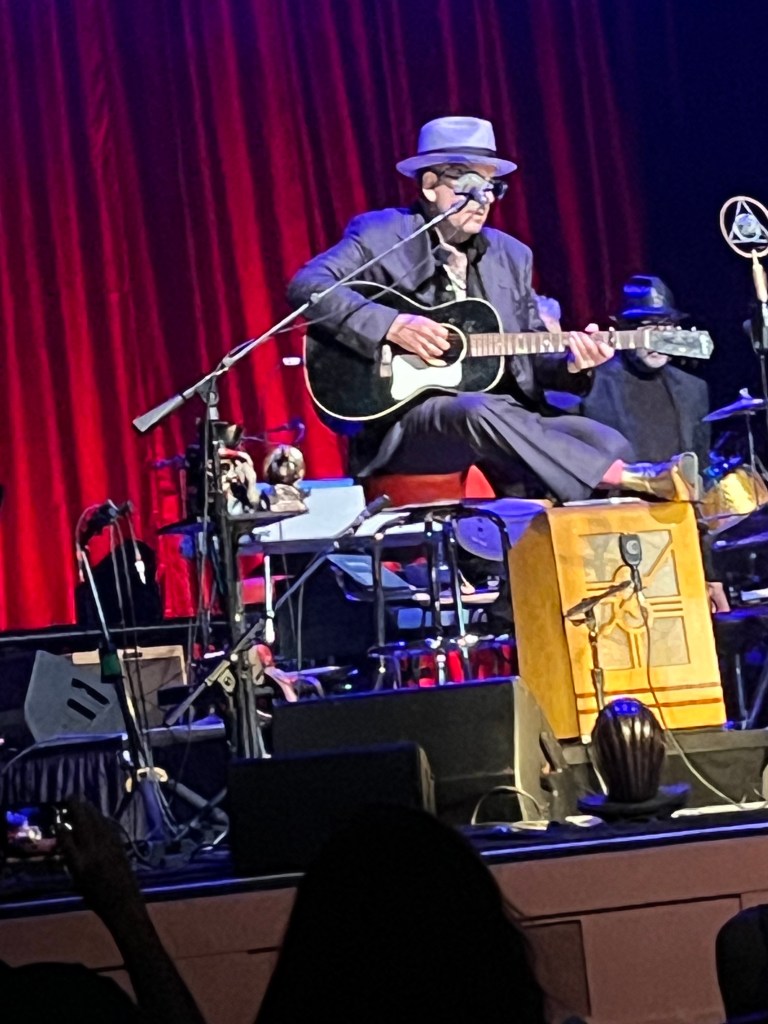

And as luck would have it, just last night I was privileged to hear my pal David Boatwright and his band Minimum Wage perform David’s song “Pee Wee Gaskins” at art reception at Redux Contemporary Art Center where Buff Ross is showing some of David’s murals that have lost their original homes in Charleston’s real estate shuffles.

The murals are so great. My favorite is a street scene in which Fredick Douglas is operating a Trolly Car that runs from White Point to the Neck.

Cool ass art is displayed throughout the building, which is located at 1054 King Street.

It’s not every day you see an ad for a James Brown inflatable sex machine sex toy.

Anyway, here’s a snippet of Minimum Wage performing “Pee Wee”Gaskins.” The iPhone video doesn’t do it justice.

[1] He’s also the namesake of an Indonesian punk rock band.

[2] It’s floundering at number 1,125,593 on the Amazon Best Sellers list, so why don’t you do a senior citizen on a fixed income a favor and order yourself one.

[3] The Osceola, which I read as an undergrad at USC