Vaudeville Meets William Faulkner Meets The Hallmark Channel

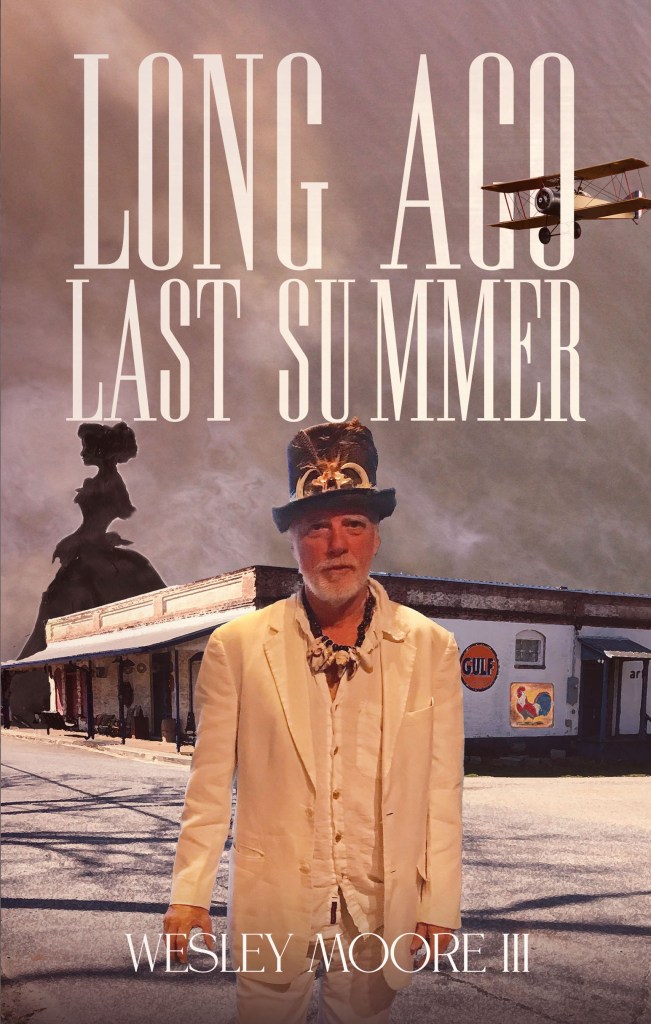

On Friday, I had my first interview involving my new book Long Ago Last Summer. Lorne Chambers, who owns the Folly Current and has an MFA in writing from the College of Charleston, met me at Chico Feo where we chatted about creative writing in general and Long Ago in particular over a couple of beers.

Occasionally, I didn’t know how to respond to Lorne’s excellent questions because Long Ago is such a strange book that it can’t be easily categorized. When you’re trying to sell something, it’s helpful to have a clear, simple message like it’s “a coming-of-age novel” or a “dystopian sci-fi epic” or “a romantic comedy.” With Long Ago Last Summer it’s more like Vaudeville meets William Faulkner meets The Hallmark Channel.

In essence, it’s a memoir, which is embarrassing enough because of the egocentricity inherent in thinking my life is so noteworthy that it warrants being shared with others. And in many ways, my life has been unadventurous. I enjoyed a long lasting, loving marriage for 38 years, a stable teaching career for 34 years, reared two successful sons, owned a succession of dogs, remarried as a widower and gained a remarkable stepdaughter. I’m well-travelled, I guess, but that’s not unusual in this day and age. To adapt a cliche: my adulthood has not been much to write home about as far as excitement goes.

On the other hand, I grew up in the segregated South, a very dark, fascinating place, a fallen civilization forever picking its scabs but then licking those newly opened wounds. The little Lowcountry town of Summerville where I grew up had two (what I’m going to uncharitably call) village idiots, among other eccentrics, like the old crone Miss Capers, religious fanatics galore, creepy good humor men, and more alcoholics per capita than most places this side of the Betty Ford Center.

Much of the book deals with an awakening consciousness that develops in a Southern Gothic setting, or, as the back cover puts it, Long Ago Last Summer “embodies the profound paradoxes of Southern culture against a landscape dotted with antebellum plantations, shotgun shacks, suburban subdivisions, Pentecostal churches, and juke joints.”

However, Long Ago is not a typical memoir in that it’s fragmentary, a collage of sorts, a mosaic, a smorgasbord or gumbo that runs the gamut from lighthearted vignettes to bleak accounts of terrible wrongdoing. If I were going to wax hyper-pretentious, I’d call it neo-Modernistic because like Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” it pieces together fragments to create a narrative held together by recurring themes. In this case, Sothern Gothicism, alienation, insomnia, and the vagaries of memory and reality.

Short fiction, verse, essays, and parodies that can stand alone out of their context occur chronologically to trace my life from its beginnings in 1952 to the present. Long Ago is, as stated in the preface, “a guided tour of the haunted houses and cobwebbed attics of my youth” followed by my college experience, my meeting and falling in love with Judy Birdsong, her illness and death, and my finding new love after her departure. In fact, included in the collection is a villanelle written by my wife Caroline that deals with Judy’s lingering presence in our marriage. In some cases, fiction is juxtaposed with non-fiction so that it’s not necessarily clear which is which.

In other words, Long Ago Last Summer is really weird, like its subject matter.

I’m appearing next week on Fox News 24’s midday show to attempt to explain all of this to viewers who may or may not have heard of TS Eliot and/or Modernism or vaudeville for that matter.

Also, weather permitting, I’m reading brief samples Monday, May 26 around 7:20 at George Fox’s open mic Soap Box at Chico Feo.

So, thoughts and prayers, y’all. I need them.