When I was a child, before the completion of I-26, there were two routes that led from Summerville to Charleston, and the two couldn’t have been more different in character. The more pleasant passage my parents called “the River Road,” Highway 61, a tree tunnel of moss-draped oaks running parallel to the Ashley River and past the antebellum plantations of Middleton, Magnolia, and Drayton Hall, which had become tourist attractions.

My parents referred to the other route, Highway 52, as the “Dual Lane” because it featured four lanes divided by a wide grassy median. It took you past the Navy Base through what we called the Charleston Neck, a narrow passage between the Cooper and Ashley Rivers, a forlorn industrial wasteland where fertilizer plants spewed thick orange smog and produced insufferable acrid odors that could make a six-year-old sick to his stomach.

If you were in a hurry, it made more sense to take Highway 52, which was faster and much safer, especially at night. I would hate to hazard a guess as to how many people lost their lives veering off 61 into one the majestic oaks that stood ever so close to the shoulder. Also, if you took the route at night, insects bombarded the windshield in non-stop splattering, making a mess, obscuring visibility. Of course, in those days, you couldn’t press a button to spray liquid and engage wipers.

Highway 52 featured a large, old, dilapidated house that my parents mistakenly thought was the Six Mile House, a notorious inn run by John and Lavinia Fisher.[1] Lavinia, who along with her husband John, was hanged 18 February 1820, became known as “the first female serial killer in the United States,” an epithet that doesn’t really trip off the tongue the way epithets should.[2] There was also a rumor that the skeleton at the Old Charleston Museum belonged to Lavinia, who had responded to her husband’s pleas that she make peace with the Lord with these memorable last words: “Cease! I will have none of it. Save your words for others that want them. But if you have a message you want sent to Hell, give it to me; I’ll carry it.”

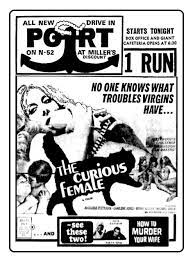

Also, the Dual Lane had drive-in movies whose screens were visible at night. Later, when I myself was driving, a triple X movie playing at the Port or North 52 could itself cause a traffic mishap.

Nevertheless, I preferred the River Road because my parents would sometimes sing duets when we took that route, and never did when we travelled the Dual Lane. Here’s one of their favorites:

I know a ditty nutty as a fruitcake

Goofy as a goon and silly as a loon

Some call it pretty, others call it crazy

But they all sing this tune:

Mairzy doats and dozy doats and liddle lamzy divey

A kiddley divey too, wouldn’t you?

Yes! Mairzy doats and dozy doats and liddle lamzy divey

A kiddley divey too, wouldn’t you?

If the words sound queer and funny to your ear, a little bit jumbled and jivey

Sing “Mares eat oats and does eat oats and little lambs eat ivy.”

Oh! Mairzy doats and dozy doats and liddle lamzy divey

A kiddley divey too, wouldn’t you-oo?

Maybe the smog or the faster traffic of the Dual Lane dissuaded them from singing. It would have been nice to own a car with a radio – or air-conditioning for that matter – but we didn’t until my friend, the late Gordon Wilson, totaled my parents’ Ford Falcon in the spring of 1971.

How did he total the car? We hit a mule that had escaped from Middleton Plantation right there on Highway 61 about ten miles north of Summerville. The mule didn’t make it, but we did, which is surprising given the Falcon didn’t have seatbelts.

Because my butt was sore from a penicillin shot, I let Gordon drive, a decision that didn’t delight my sometime-singing parents.

[1]The Six Mile House was burned to the ground in 1820.

[2] C.f., “the Butcher of Baghdad,” “the Teflon Don,” etc.