In my boyhood, before adolescence, I began each day by retrieving the newspaper from what we called the front porch, though, in truth, it was more like an elevated stoop, a 6 x 6 concrete slab. If there were a big story, like the suicide of Marilyn Monroe, I’d read it right there, or if there were an untelevised sporting event I cared about, I’d rip open the sports section to discover the outcome. That was the case on 25 February 1964 when Cassius Clay, as he was called in those days, upset Sonny Liston for the Heavyweight Championship of the World. It was the outcome I had fervently hoped for, and it had happened, despite 7 to 1 odds. I remember sitting on the steps of the stoop, reading the account that included the accusation that Liston had thrown some type of blinding powder in Clay’s eyes.

In my boyhood, before adolescence, I began each day by retrieving the newspaper from what we called the front porch, though, in truth, it was more like an elevated stoop, a 6 x 6 concrete slab. If there were a big story, like the suicide of Marilyn Monroe, I’d read it right there, or if there were an untelevised sporting event I cared about, I’d rip open the sports section to discover the outcome. That was the case on 25 February 1964 when Cassius Clay, as he was called in those days, upset Sonny Liston for the Heavyweight Championship of the World. It was the outcome I had fervently hoped for, and it had happened, despite 7 to 1 odds. I remember sitting on the steps of the stoop, reading the account that included the accusation that Liston had thrown some type of blinding powder in Clay’s eyes.

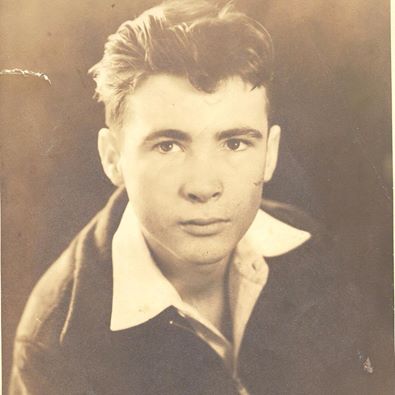

My father had been an amateur boxer in his youth, a welterweight who developed his skills on the sidewalks of Spring Street in Charleston, SC, during the Depression. Every Friday night he’d watch the fights broadcast on the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports as he sat on the sofa smoking cigarette after cigarette, leaning into the television, screaming suggestions to the combatants even though they were hundreds of miles away at Madison Square Garden. He had bought my brother and me boxing gloves and roped off the living room and taught us how to box, to crouch, to throw punches with our “hips” instead of our “arms.” I hated it, being at once weak, blinky, and adverse to pain.

But I did enjoy watching the matches, and we liked “Cassius Clay,” because he was funny, brash, clever, a rhymer, and, I’m sorry to say, perhaps because he was “light-skinned,” unlike Sonny Liston and Joe Frazier. Clay, and later, Ali, was also too aware of this distinction in skin tones. Here’s a snippet from Robert Lipsyte’s superb obituary from the Times:

But Ali had his hypocrisies, or at least inconsistencies. How could he consider himself a “race man” yet mock the skin color, hair and features of other African-Americans, most notably Joe Frazier his rival and opponent in three classic matches? Ali called him “the gorilla,” and long afterward Frazier continued to express hurt and bitterness.

Ali would also play upon racial and ethnic stereotypes. Here is a joke he told at a fundraiser in Louisville in 2005:

“If a black man, a Mexican and a Puerto Rican are sitting in the back of a car, who’s driving? Give up? The po-lice.”

And here he is explaining to a Soviet reporter in 1960 why he’s proud to be an American citizen.

“It may be hard to get something to eat sometimes, but anyhow I ain’t fighting alligators and living in a mud hut.”

In some ways, like my father, he was a man of his times.

However, even though these quips might have gotten Ali dis-invited from a speaking engagement at Oberlin, in the course of his life, he displayed more courage than any other athlete I can think of. Ali was a man of his convictions, willing to make unpopular brand-tarnishing decisions like converting to the Nation of Islam and facing the prospect of prison for refusing to be drafted into the Viet Nam War. “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong,” he said, adding, “They ain’t never called me no [racial expletive].”

And Ali sacrificed three prime years when boxing commissions around the country stripped him of his titles, and although the backlash was fierce and many journalists refused to call him by his new name, he earned the respect over time for his principled stands, and, even my father, not exactly a devotee of Malcolm X, continued to pull for Ali upon his return to the ring.

Perhaps it was because Ali was such a beautiful, graceful fighter, poetry –not doggerel — in motion or because he was so witty, possessed such a generous spirit, and these attributes transcended by father’s homegrown prejudices. Later in life Ali said, “Color doesn’t make a man a devil. It’s the heart and soul and mind that count. What’s on the outside is only decoration.”

At any rate, it says something positive about our nation that at his death Muhammad Ali was virtually universally admired by his fellow citizens, even, it would seem, Donald Trump.

All leave you with this ditty from the great Bob Dylan:

I was shadow-boxing earlier in the day

I figured I was ready for Cassius Clay

I said “Fee, fie, fo, fum, Cassius Clay, here I come

26, 27, 28, 29, I’m gonna make your face look just like mine

Five, four, three, two, one, Cassius Clay you’d better run

99, 100, 101, 102, your ma won’t even recognize you

14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, gonna knock him clean right out of his spleen”