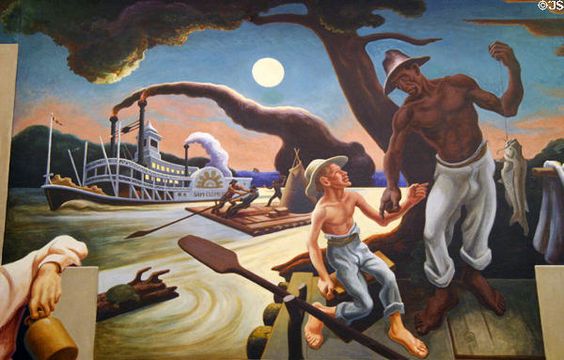

After reading Dwight Garner’s laudatory review of Percival Everett’s James, I was eager to check it out, especially since I’m a huge fan of Huckleberry Finn.

Here’s a snippet of Garner’s paean:

Percival Everett’s majestic new novel, James, goes several steps further. Everett flips the perspective on the events in Huckleberry Finn. He gives us the story as a coolly electric first-person narrative in the voice of Jim, the novel’s enslaved runaway. The pair’s adventures on the raft as it twisted down the Mississippi River were largely, from Huck’s perspective, larks. From Jim’s — excuse me, James’s — point of view, nearly every second is deadly serious. We recall that Jim told Huck, in Twain’s novel, that he was quite done with “adventures.”

Garner goes on to say, “This s Everett’s most thrilling novel, but also his most soulful.”

Alas, when reading James, I was never able to suspend my disbelief, to lose myself in the flow of action and forget that the narrative I was reading was a fictive construction. In his retelling of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim, Everett creates the conceit that the antebellum argot of slaves, the “Else’n they takes you to the post and whips ya[s]” is a linguistic ruse to appease the white population by making them feel superior. The narrator James (aka Jim) speaks (and thinks) in English so standard that he uses “one” instead of “you.” In short, for me the novel is a contrivance; it’s created in a way that seems artificial and unrealistic.

Everett’s relating the events from James’ perspective in easy-to-decipher prose makes a lot of practical sense; however, the regionless diction of the retelling of Jim and Huck’s escape robs Jim of a breathing individual’s voice –– he could be from 21st Century Dayton, Ohio –– there are no quirks in his phraseology, no flashes of individuality, few regional linguistic markers, which divorces him from time and place and therefore relegates him into the status of a character in a novel rather than a person whom we believe is real.

That said, Everett does an outstanding job of effectively depicting the horrors of slavery, the never-ending degradation, the perennial fear of having your family disbanded, the horrors of being horsewhipped, the constant verbal abuse. And the novel, especially after James hooks up with a minstrel show, becomes a real page turner, a sort of thriller with cliffhanging chapter endings as he and Huck manage a series of hairbreadth escapes a la The Perils of Pauline. Everett also creates a rich array of colorful characters that you care enough to keep reading, though you might grow a bit weary of the episodic nature of the plot bequeathed by Clemons.

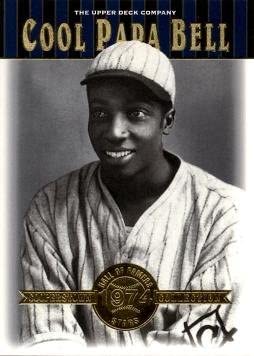

I couldn’t help unfavorably comparing James to James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird, which is also narrated by a slave, Little Onion, who is “liberated” by the historical abolitionist John Brown.

Here’s Little Onion describing his liberator:

The old face, crinkled and dented with canals running every which way, pushed and shoved up against itself for a while, till a big old smile busted out from beneath ’em all, and his grey eyes fairly glowed. It was the first time I ever saw him smile free. A true smile. It was like looking at the face of God. And I knowed then, for the first time, that him being the person to lead the colored to freedom weren’t no lunacy. It was something he knowed true inside him. I saw it clear for the first time. I knowed then, too, that he knowed what I was – from the very first.

This is a person talking, not the idea of a person talking, which creates a depth of character that James lacks.

Compare McBride’s description with this:

I was afraid of the men, but I was considerably more afraid of the dogs I’d heard coming our way. I could only imagine that they were after me, and so I was left confused by the presence of these two white men in our boat. Adding to the absurdity was the fact that they were opposite in nearly every way. The older man was very tall and gaunt, while the younger was nearly as short as Huck and fat. The younger had a head full of dark hair. The older was completely bald.

That’s not what I would call “cooly electric first person narrative.” In fact, when I taught composition, I would not allow my students to use the phrase “was the fact that.”

But, hey, look, as I’ve said elsewhere and often, writing a novel is a very difficult undertaking, and James is well worth reading, even though it falls short of my censorious standards for the high praise it has received. It’s an audacious effort to reconfigure the novel that Hemingway credited with being the root of “all American literature.” Also, the idea of seeing Huck’s world from Jim’s perspective is existentially cool, underscoring Hamlet’s observation that “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

I’d give it a B+ overall.