The summer before my eighth grade year, I started hanging out with nerdy high school sophomores who, rather than drinking and fornicating, behaved like tweens, tweens who could drive at night but who also did dumb stuff like chunking lit cherry bombs out of windows of moving vehicles with fireworks galore on board. I didn’t lie to my mother – my father was a distant figure, not involved with my comings and goings – I’d tell Mama I’d be riding around town with Ricky and Dave, and she’d say okay but be home by ten. I can’t remember my precise curfew, probably ten. In high school it was 11:30.

I have no memory of what we talked about on those hours-long drives, but I do remember cherry bombs exploding underwater when we’d stop at a bridge, and I remember the circuit we’d take, heading out Trolley Road to Dorchester, taking a left, then another left that took us to Ladson, skirting a subdivision called Tranquil Acres where my crush, blandly pretty, super-intelligent Laura Alexander lived with her Air Force Lt. Colonel of a father, her mother, and whatever siblings she may have had.

We’d head back along that stretch of Hwy 78 towards Twin Oaks, or sometimes take Lincolnville Road back to our subdivision. This looping drive introduced me to a strange, incongruous world of manufactured houses with meticulously tended gardens and churches, churches, churches, tiny concrete block churches, every half-mile on both sides of the road, with exotic names rife with schism, like the Second Church of God Consecrated in Holy Blood of the Nazarene.[1]

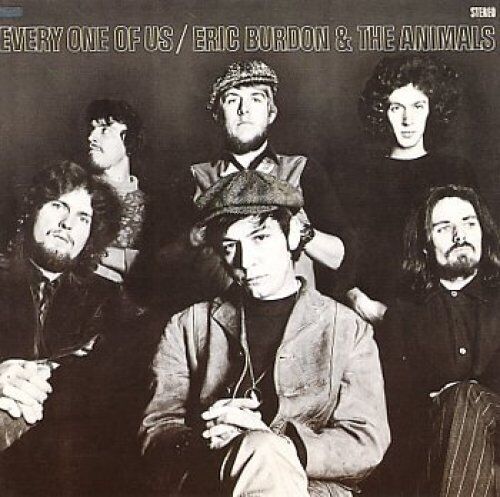

My high school friend Ricky was the product of what some called in those days “a broken home,” and he rarely saw his father, an airline pilot who showered him with gifts whenever they did get together. His mother worked, so we could hang out at his house and listen over and over and over again to The Animals Greatest Hits, which ended up being a revelation to me, hearing Eric Burdon sing “House of the Rising Sun” in a voice that sounded as if he himself could have been born in Summerville, singing in baritone with a hint of Gullah about things much deeper than you found in the Monkees’ catchy love songs.

Ricky had two sisters, one off at college and another maybe a junior or senior, a year or two older. Her name was Penelope, and one afternoon, she jumped out of a closet in her institutional white bra and panties screaming “boo!” If this were a graphic novel instead of po-dunk memoir, I’d have my auburn hair porcupining like I’d received an electric shock. She howling, laughing, sprinted to her room, butt jiggling, and slammed the door. It was weird, but cool, yet it never happened again. She spent a lot of time in her room alone. She was a brunette, very good looking, but not all that popular.

The older sister, on the other hand, a coed at the University of South Carolina, had been a Summerville High School superstar, the homecoming queen, maybe.[2] I met her once with her boyfriend at Ricky’s, the boyfriend Hollywood good-looking and the son of the woman who four years later would be my English teacher, the model for Mrs. Barrineau in Today, Oh Boy. I knew about this star couple because my aunt Virginia, only 6 years older than I-and-I[3], was in their graduating class. I felt as if I were hanging with celebrities, and they shocked me by striding up to Ricky’s mama’s bar and pouring themselves some kind of whiskey over ice. Ricky showed my future teacher’s son of Best of the Animals‘ album cover, and he said that “House of the Rising Sun” was the only song he liked, and I thought to myself what about “We Got to Get Out of This Place,” what about “It’s My Life,” what about “Please Don’t Let Me Misunderstood?”

It was a memorable summer.

[1] Or something like that.

[2] None of my yearbooks have survived my bopping from place to place, so I can’t confirm.

[3] This affectation, using the Rasta hyphenated pronouns, does come in handy here where I can avoid the conversational, grammatically incorrect “me” yet sound hip.

You can purchase Today, Oh Boy HERE.