Obviously, I’m a huge fan of the novel as a literary genre. Just the other day, I was explaining to someone at Chico Feo how literary novels can be treasure troves of vicarious experience because they feature lifelike characters who behave like real people. These novels aren’t didactic, but by co-experiencing Emma Bovary’s tragic vanity, you might glean that fabricating a persona through conspicuous consumption is not the way to go.

In other words, rather than discovering through personal experience that purchasing a vintage Rolls Royce Silver Shadow will likely destroy your credit and leave you destitute, you can witness rabid Emma’s spending sprees, yet not personally suffer the consequences of her foolhardiness.

Of course, part of Emma’s problem is that she mistook the romance novels she misread as real life, the way I misperceived the Long Ranger as real life when as a five year old in Biloxi, Mississippi, I leapt from the top of my chest of drawers onto a rocking horse that catapulted me face first on a wooden floor, a hard lesson (literally) in appreciating the difference between illusion and reality. If I had read about a fool boy doing that in a book, I never would have tried it myself.

As Laurence Perrine states in his wonderful textbook Literature, Sound, Structure, and Sense, “inexperienced readers” [of commercial fiction] want their stories to be mainly pleasant. Evil, danger, and misery may appear in them, but not in such a way that they need be taken really seriously or are felt to be oppressive or permanent.” A steady diet of happy endings could inculcate in an unsophisticated reader (or movie goer) the misperception that things always work out.

In other words, evil, danger, and misery need to be taken very seriously.[1]

Of course, the puritans, those “vice crusaders farting through silk,” who have taken over the schoolboards in our budding authoritarian state are aware of the potential for fiction to alter attitudes. For example, reading a novel that portrays a gay teenager as a decent, sincere person doing her best to navigate the perilous journey of adolescence might suggest to a homophobic sixteen-year-old that gay people are worthy of respect and empathy.

The vice crusaders certainly don’t want that.

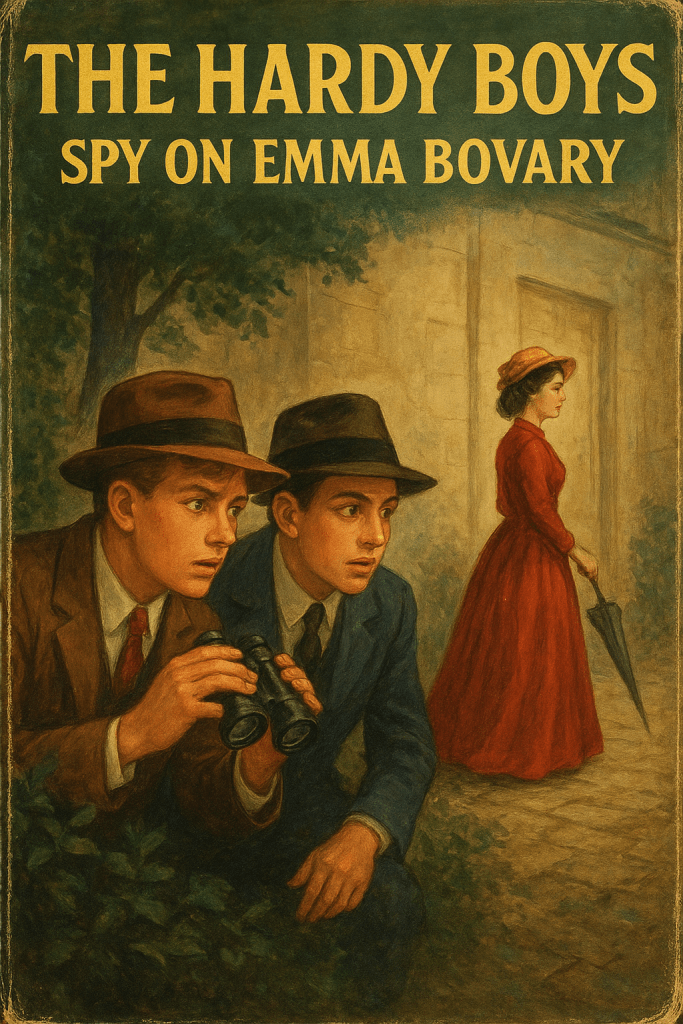

Just for the hell of it, after rereading Jo Humphrey’s brilliant but under-appreciated novel Fireman’s Fair –set in the disorienting wreckage of post Hurricane Hugo Charleston – I switched to escapist fiction, and for the first time since I read it out loud to my sons, ripped through the Hardy Boys series’ first title The Tower Treasure.

Whereas Jo’s book featured an array of well-rounded characters, The Tower Treasure trots out a series of underdeveloped static, one-dimensional mouthpieces: the indulgent dad, ace detective Fenton Hardy, his wife, a homemaker who doesn’t merit a first name because all she does is make sandwiches, and the boys themselves, Joe and Frank, and their various “chums” and female friends.

(A sidenote to budding fiction writers: avoid elaborate dialogue tags like “‘You’re elected,’ the others chorused.'”[2])

Truth be told, I actually enjoyed The Tower Treasure, which, despite its flaws, boasts a fast-moving plot that creates temporary suspense, but I never feared that the one of the two helmetless boy detectives would crash his motorcycle and end up a paraplegic.

And, of course, the novel also offers sociological insights into the attitudes of White people in the early 20th century and how those attitudes changed as the series progressed through the decades, e.g., Mrs. Hardy’s earning a first name –– Laura –– and eventually working outside the home as research librarian.

Someone (but not me) should do a scholarly paper on how the Hardy Boys novels reflect the social mores of their times and how those changing mores are reflected in changes in the novels’ depiction of the white enclave of Bayport, a city in New York in some novels and New Jersey in others.

After all, the ways things are going here in the dumb-downed US, the Hardy Boys may replace Animal Farm as required reading.

[1] Just last week a cook a Chico Feo, Jorge, who had a valid visa and a green card, was apprehended by ICE as he played by the rules by visiting his immigration office. ICE handcuffed him and swept him away to god knows where. I don’t foresee a series of hairbreadth escapes in his future but, rather, disorienting displacement, maltreatment, in sum, a horrible existence. A novel dramatizing his sad journey could offer insights into the human condition; however, although an action novel depicting his escaping might be fun to read, it would literally be escapism, a means to avoid our everyday humdrum.

[2] That the six “youths” in the scene all “chorus” the exact phrase “you’re elected” is distracting and Hindenburgs my suspension of disbelief.