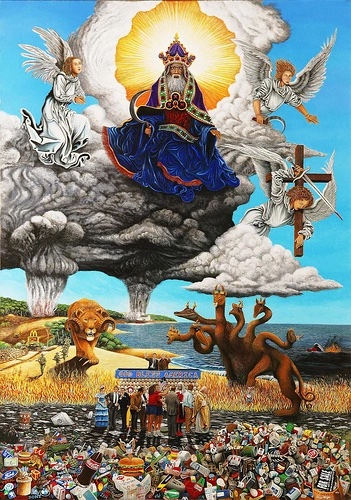

Apocalypse by Adrian Kenyon

Donald Trump has dubbed his rambling speeches “the weave,” claiming that if you connect the dots of his zigzags, a unified picture appears. So I thought I’d give it a try myself.

Here goes.

The other night, after suffering through a self-righteous, ill-informed screed from a Facebook follower, I found myself listening to Bob Dylan’s masterful protest song “Hurricane,” a cinematic narrative recounting the arrest and trial of Rubin Hurricane Carter, a boxer wrongly convicted of a triple homicide in 1966 in Patterson, New Jersey.

Meanwhile, far away in another part of town

Rubin Carter and a couple of friends are drivin’ around

Number one contender for the middleweight crown

Had no idea what kinda shit was about to go down

When a cop pulled him over to the side of the road

Just like the time before and the time before that

In Paterson that’s just the way things go

If you’re black you might as well not show up on the street

‘Less you want to draw the heat

Near the end of the song Dylan sings,

How can the life of such a man

Be in the palm of some fool’s hand?

To see him obviously framed

Couldn’t help but make me feel ashamed to live in a land

Where justice is a game

Now all the criminals in their coats and their ties

Are free to drink martinis and watch the sun rise

While Rubin sits like Buddha in a ten-foot cell

An innocent man in a living hell

As I was listening, the long gone idealism of the 60s came to mind. Dylan himself — and Joan Baez –performed at the March on Washington, sharing the stage with Martin Luther King. They heard firsthand the “I Have a Dream Speech.” They’re both still alive sixty-one years later.

In 1963, the American people considered communism the greatest threat to the nation’s sovereignty, and the Soviet Union was our greatest enemy whose spy agency the KGB eventually became the employer and training ground for Vladimir Putin, whom Donald Trump so idolizes, along with Kim Jong Un, the North Korean dictator.

According to Trump, outside forces like Russia and North Korea aren’t the greatest threat to American sovereignty; no, it’s “the enemy within,” American citizens, news organizations, and celebrities tarred with the paradoxical disapprobation “woke.” It’s Joe McCarthy redux, and McCarthy’s corrupt lawyer Roy Cohn was Donald Trump’s mentor.

Trump and his followers bring to mind WB Yeats’s lines from “The Second Coming”:

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Fueled by the fifth deadly sin wrath, these resentful white supremist faux Christian cultists seem to prefer a dictatorship of oligarchs to the teachings of their would-be Savoir who famously preached

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.

Meanwhile,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned.

Connect these dots and what do you get?

[a] rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouch[ing] towards Bethlehem to be born.