Antidepressant by Mirjana-Veljovic

In college, back in the fall of 1972, my sophomore poetry teacher assigned our class the task to compile an anthology of contemporary poems that revolved around a common theme. I chose despair because I reckoned that depression might be a common theme for poets, a notoriously withdrawn and navel-gazing lot. I figured poems of despair, unlike, say, political poems or poems dealing with domestic bliss, would make for easier harvesting because they would exist in greater abundance.

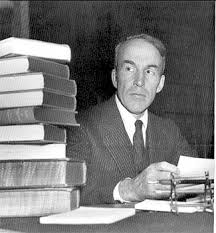

So, I checked out anthologies and skimmed poem titles and promising poems hoping to amass thirty or so specimens to satisfy the minimum requirement. In 1972, Auden and MacLeish were alive, Sylvia Plath less than a decade dead, Anne Sexton about to kill herself in a couple of years, so many of the poems I looked at had been written mid-century.

Of course, I have lost my anthology, which was hand written and received a B (likely the lowest grade given), but I do remember two of the poems I included. One was Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening,” whose rhymes and rhythms I liked and whose rather childish message was right up my cynical alley:

I walked out one evening,

Walking down Bristol Street,

The crowds upon the pavement

Were fields of harvest wheat.

And down by the brimming river

I heard a lover sing

Under an arch of the railway:

‘Love has no ending.

‘I’ll love you, dear, I’ll love you

Till China and Africa meet,

And the river jumps over the mountain

And the salmon sing in the street,

‘I’ll love you till the ocean

Is folded and hung up to dry

And the seven stars go squawking

Like geese about the sky.

‘The years shall run like rabbits,

For in my arms I hold

The Flower of the Ages,

And the first love of the world.’

But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

‘O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time.

‘In the burrows of the Nightmare

Where Justice naked is,

Time watches from the shadow

And coughs when you would kiss.

‘In headaches and in worry

Vaguely life leaks away,

And Time will have his fancy

To-morrow or to-day.

‘Into many a green valley

Drifts the appalling snow;

Time breaks the threaded dances

And the diver’s brilliant bow.

‘O plunge your hands in water,

Plunge them in up to the wrist;

Stare, stare in the basin

And wonder what you’ve missed.

‘The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed,

And the crack in the tea-cup opens

A lane to the land of the dead.

‘Where the beggars raffle the banknotes

And the Giant is enchanting to Jack,

And the Lily-white Boy is a Roarer,

And Jill goes down on her back.

‘O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress:

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.

‘O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You shall love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.’

It was late, late in the evening,

The lovers they were gone;

The clocks had ceased their chiming,

And the deep river ran on.

WH Auden

The other poem I remember including, a much better poem, is Archibald McLeish’s, “You, Andrew Marvell.” As it turned out, the very next year I would hear MacLeish read the poem in person, he who was born the year that Tennyson died.

You, Andrew Marvell

And here face down beneath the sun

And here upon earth’s noonward height

To feel the always coming on

The always rising of the night:

To feel creep up the curving east

The earthy chill of dusk and slow

Upon those under lands the vast

And ever climbing shadow grow

And strange at Ecbatan the trees

Take leaf by leaf the evening strange

The flooding dark about their knees

The mountains over Persia change

And now at Kermanshah the gate

Dark empty and the withered grass

And through the twilight now the late

Few travelers in the westward pass

And Baghdad darken and the bridge

Across the silent river gone

And through Arabia the edge

Of evening widen and steal on

And deepen on Palmyra’s street

The wheel rut in the ruined stone

And Lebanon fade out and Crete

High through the clouds and overblown

And over Sicily the air

Still flashing with the landward gulls

And loom and slowly disappear

The sails above the shadowy hulls

And Spain go under and the shore

Of Africa the gilded sand

And evening vanish and no more

The low pale light across that land

Nor now the long light on the sea:

And here face downward in the sun

To feel how swift how secretly

The shadow of the night comes on …

Archibald MacLeish

Sometimes, like this morning, when sleep has stood me up and I don’t feel so hot mentally, I seek a dark poem with which I’m not familiar as a way to commiserate with a stranger who might have it worse than I-and-I.

And lo and behold I discovered this poem by Jane Kenyon a couple of hours ago. Jane Kenyon, who died of leukemia, was the subject of the superb book-length elegy Without by her husband Donald Hall. I read the poem in the New Yorker in the mid-Nineties right after I had recovered from a serious case of clinical depression. You can read one of the poems from the collection here, but I would love to share with you Jane’s poem, which I find profound and beautiful:

HAVING IT OUT WITH MELANCHOLY” BY JANE KENYON

-

FROM THE NURSERY

When I was born, you waited

behind a pile of linen in the nursery,

and when we were alone, you lay down

on top of me, pressing

the bile of desolation into every pore.

And from that day on

everything under the sun and moon

made me sad — even the yellow

wooden beads that slid and spun

along a spindle on my crib.

You taught me to exist without gratitude.

You ruined my manners toward God:

“We’re here simply to wait for death;

the pleasures of earth are overrated.”

I only appeared to belong to my mother,

to live among blocks and cotton undershirts

with snaps; among red tin lunch boxes

and report cards in ugly brown slipcases.

I was already yours — the anti-urge,

the mutilator of souls.

- BOTTLES

Elavil, Ludiomil, Doxepin,

Norpramin, Prozac, Lithium, Xanax,

Wellbutrin, Parnate, Nardil, Zoloft.

The coated ones smell sweet or have

no smell; the powdery ones smell

like the chemistry lab at school

that made me hold my breath.

- SUGGESTION FROM A FRIEND

You wouldn’t be so depressed

if you really believed in God.

- OFTEN

Often I go to bed as soon after dinner

as seems adult

(I mean I try to wait for dark)

in order to push away

from the massive pain in sleep’s

frail wicker coracle.

- ONCE THERE WAS LIGHT

Once, in my early thirties, I saw

that I was a speck of light in the great

river of light that undulates through time

I was floating with the whole

human family. We were all colors — those

who are living now, those who have died,

those who are not yet born. For a few

moments I floated, completely calm,

and I no longer hated having to exist

Like a crow who smells hot blood

you came flying to pull me out

of the glowing stream.

“I’ll hold you up. I never let my dear

ones drown!” After that, I wept for days.

- IN AND OUT

The dog searches until he finds me

upstairs, lies down with a clatter

of elbows, puts his head on my foot.

Sometimes the sound of his breathing

saves my life — in and out, in

and out; a pause, a long sigh. . . .

- PARDON

A piece of burned meat

wears my clothes, speaks

in my voice, dispatches obligations

haltingly, or not at all.

It is tired of trying

to be stouthearted, tired

beyond measure.

We move on to the monoamine

oxidase inhibitors. Day and night

I feel as if I had drunk six cups

of coffee, but the pain stops

abruptly. With the wonder

and bitterness of someone pardoned

for a crime she did not commit

I come back to marriage and friends,

to pink fringed hollyhocks; come back

to my desk, books, and chair.

- CREDO

Pharmaceutical wonders are at work

but I believe only in this moment

of well-being. Unholy ghost,

you are certain to come again.

Coarse, mean, you’ll put your feet

on the coffee table, lean back,

and turn me into someone who can’t

take the trouble to speak; someone

who can’t sleep, or who does nothing

but sleep; can’t read, or call

for an appointment for help.

There is nothing I can do

against your coming.

When I awake, I am still with thee.

- WOOD THRUSH

High on Nardil and June light

I wake at four,

waiting greedily for the first

note of the wood thrush. Easeful air

presses through the screen

with the wild, complex song

of the bird, and I am overcome

by ordinary contentment.

What hurt me so terribly

all my life until this moment?

How I love the small, swiftly

beating heart of the bird

singing in the great maples;

its bright, unequivocal eye.

Jane Kenyon

Happy Hump Day!