In times of trouble, it’s not Mother Mary who comes to me, but Marcus Aurelius whose Meditations provide a practical response to the woes we face, and there’s no question that because of the election of Donald J Trump, the Western World is going to go through some things, especially Eastern and Western Europe. My father used to say that Russia will take us over without firing a shot. It certainly seems as if he might have been right.

Here, in the US, we have a patchwork of abortion laws, some so strict that so-called pro-lifers would rather a woman bleed to death than receive treatment during miscarriage. Trump has promised to put crackpot Robert Kennedy in charge of health and Elon Musk in charge of transforming the civil service into a Soviet-like bureaucracy of yes men. Most galling to me is that this adjudicated rapist, convicted felon, incorrigible liar and his servile minions are now in full celebration mode, not to mention that my faith of the good will of the American people has been severely compromised.

Yes, I’m heartbroken, but I am powerless at the moment to change the situation; however, I do have the power to herd my thoughts from the edge of a cliff to safer ground.

Here’s Aurelius:

“The first rule is to keep an untroubled spirit. The second is to look things in the face and know them for what they are.”

Of course, maintaining an untroubled spirit is much easier said than done.[1] However, “if you are pained by external things,” as Aurelius writes, ‘it is not they that disturb you, but your own judgement of them. And it is in your power to wipe out that judgement now.”

By judgement, I think he means your thinking of them, dwelling on them at the expense of the mundane joys of life, like looking up and seeing a formation of geese flying overhead, listening to Lester Young speaking through his tenor saxophone, enjoying the taste of olives plucked from a bowl that has been cured in a kiln, the bowl, a thing of beauty, which guides your thoughts to Keats’ great ode in which he sings, “a thing of beauty is a joy forever.”

Our moments are too precious to squander in barren speculation. What will be will be. I’ll attempt to employ what the Buddhists call mindfulness. I’ll try to pay attention to what is in front of me rather than the agonizing over what may or not be. I’ll attempt not to dwell in the shadows dark speculations.

In short,

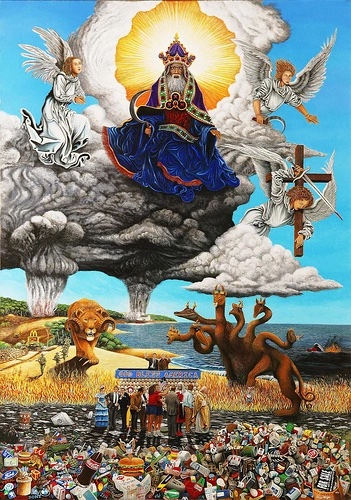

Live a good life. If there are gods and they are just, then they will not care how devout you have been, but will welcome you based on the virtues you have lived by. If there are gods, but unjust, then you should not want to worship them. If there are no gods, then you will be gone, but will have lived a noble life that will live on in the memories of your loved ones.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

To a Friend Whose Work Has Come to Nothing

Now all the truth is out,

Be secret and take defeat

From any brazen throat,

For how can you compete,

Being honor bred, with one

Who were it proved he lies

Were neither shamed in his own

Nor in his neighbors’ eyes;

Bred to a harder thing

Than Triumph, turn away

And like a laughing string

Whereon mad fingers play

Amid a place of stone,

Be secret and exult,

Because of all things known

That is most difficult.

WB Yeats

[1] Here’s a link to a piece I wrote called “The Art of Not Thinking.”