A dozen years ago when I chaired Porter-Gaud’s English Department, I received a parental email so shrill it made a banshee keen sound like Barry White love talking.

One of my colleagues in the New Testament unit in 8th grade English had assigned the Gospel of Thomas, a compilation of “Jesus sayings” declared heretical by the early Church Fathers Origen and Hippolytus of Rome. Here’s an example:

His disciples said: On what day will you be revealed to us, and on what day shall we see you? Jesus said: When you unclothe yourselves and are not ashamed, and take your garments and lay them beneath your feet like the little children (and) trample on them, then [you will see] the Son of the Living One, and you will not be afraid.

Gospel of Thomas Saying 37

Anyway, this email (which I long ago deleted) seemed to have originated from the windblown sands of ancient deserts, the Land of Thou Shall Not, the land where graven images are taboo, where Jezebels are stoned to death. The email actually contained this suggestion: “(see Origen).”[1]

* * *

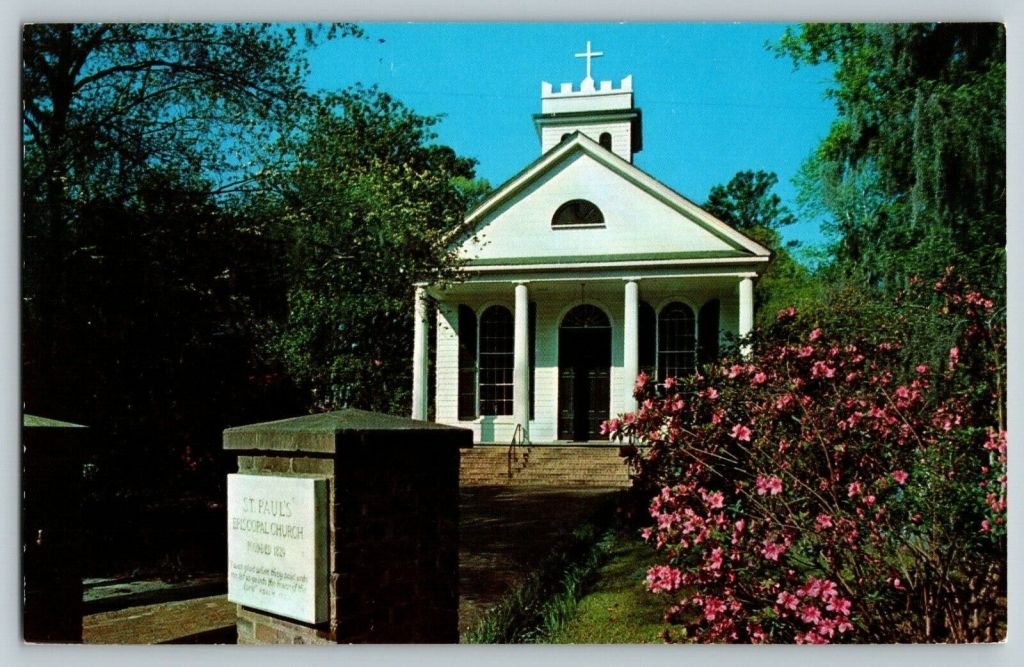

On the Monday morning after my confirmation c. 1964, Bishop Gray Temple administered to me my first communion in the church pictured above, and my fellow communicates and I breakfasted afterwards with the Bishop and my parish priest Steve Skardon at the (unfortunately named but elegant) Squirrel Inn in Summerville, South Carolina. The ritual had seemed (sort of) holy to me, and at breakfast the men wearing the collars were not in the least bit patronizing. They were literally gentle men. Afterwards, Father Skardon dropped me off to school. He respected my father, who was not a gentle man, who saw the world much differently than Father Skardon, but my father respected Steve as well. In fact, the last time I saw Father Skardon was at a wedding in Florence in 1977, and the first thing he asked me was how my father was doing.

He and Gray Temple possessed a quiet confidence. The sins of the flesh that they knew we would commit in the next few years did not terrify them. The Gospel Of Thomas did not enrage them. They understood Thomas was an alternative text that shared roots with the canonical gospels in that long process from word of mouth into writing. They understood that Yahweh-Nazarene-Ghost did not literally oversee translations from Aramaic to Greek nor guided the hands of scribes throughout the centuries to insure no deviation of the texts. They possessed imaginations. They had embraced the Enlightenment and understood that myths can convey the most profound truths. In other words, they understood that the Bible was not literally true. If asked if Augustus Caesar ever decreed that you had to travel back to your hometown to be counted in a census, they would have said no, that was an invention to establish Jesus in the line of David, etc.

And, I suspect, they realized that despite their canonizations, Origen and Hippolytus of Rome, were, not to put too fine a point on it, fanatical to the point of insanity, and that it would not be such a good idea to have their millennium-old decrees dictating 21st Century curricula.

***

Steve Skardon

Not long after my first communion, I witnessed a remarkable act of courage, Father Skardon preaching integration to a seething segregationist congregation.

Although I stupidly held my father’s bigoted viewpoint at the time, this man standing before a hostile audience pronouncing what was heresy to them made a profound impression on me. I am ashamed now to admit that I didn’t like what he was saying – that Blacks deserved the same social and political rights that whites possessed – but his demeanor as he calmly faced those angry parishioners profoundly affected me: Summerville’s own Atticus Finch.

Having a half-Baptist family, I felt much more comfortable at St. Paul’s than at Summerville Baptist, where the carpets were blood red and the smell antiseptic. St. Paul’s offered the redolent pleasures of candle scent; Chanel No. 5; and the occasional exhalation of last night’s Makers Mark, the somewhat sweet but unpleasant odor of sin. Our Church League Basketball team had the words “Episcopal Fifths.” on our jerseys. Father Skardon did not seem to mind.

Those harsh life-negating deserts of origin/Origen seemed thousands of years and thousands of miles distant. The liturgy and accompanying rituals were life affirming. The sermons tolerant, forgiving. The cerebral cortex (logical discourse) rather than the brain stem (babbling in tongues, etc.) held precedence.

After all, we lived in a semi-tropical climate.

[1] Origen, a 3rd Century Christian scholar, is the poster Eunuch for taking Biblical texts too literally, e.g., “there are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of God.” Or, to put it another way, “if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out and cast it from thee.” To cut to the chase, both his left and right testicles offended him, so he castrated himself or had a friend castrate him. Origen had condemned the Gospel of Thomas, as heresy hence the suggestion to consult his writings.