On his podcast, David Watson interviews Caroline and me about my novel “Today, Oh Boy,” teaching adolescents, and the nature of time, plus a lot of other stuff.

Month: March 2024

Functional Allusions

I’ve always been a big fan of allusions because they infuse whatever the writer is conveying with even more meaning, offering subtext or cross references that deepen. If you don’t pick up on the references, no harm done. If you do, God is in his heaven, and all’s right with the world.[1]

Here’s what I’m talking about: in the Richard Wilbur ‘s poem “A Late Aubade,” the speaker is trying to talk his lover into cutting class so they can continue to lie in bed in what I’m assuming is an interlude between another session of lovemaking.

Here’s, as the vulgar say, the money shot:

It’s almost noon, you say? If so,

Time flies, and I need not rehearse

The rosebuds-theme of centuries of verse.

If you must go,Wait for a while, then slip downstairs

And bring us up some chilled white wine,

And some blue cheese, and crackers, and some fine

Ruddy-skinned pears.

Rehearse, as in re-hearse, as in death mobiles, black limousines, but then – BAM – the allusion to Robert Herrick’s, “To the Virgins to Make Much of Time”:

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today

Tomorrow will be dying.

Carpe Diem!

Or, as Andrew Marvell put it:

The grave’s a fine and private place,

But none, I think, do there embrace.

ILLUSTRATION: YAO XIAO

[1] BTW, I wish I did, but I don’t believe in anthropomorphic Semitic deities. “God is in his heaven” is an allusion, albeit an ironic one, to the Victorian poet Robert Browning.

AI Don’t Scare Me (Yet)

Blind Girl Walking by Wesley Moore III

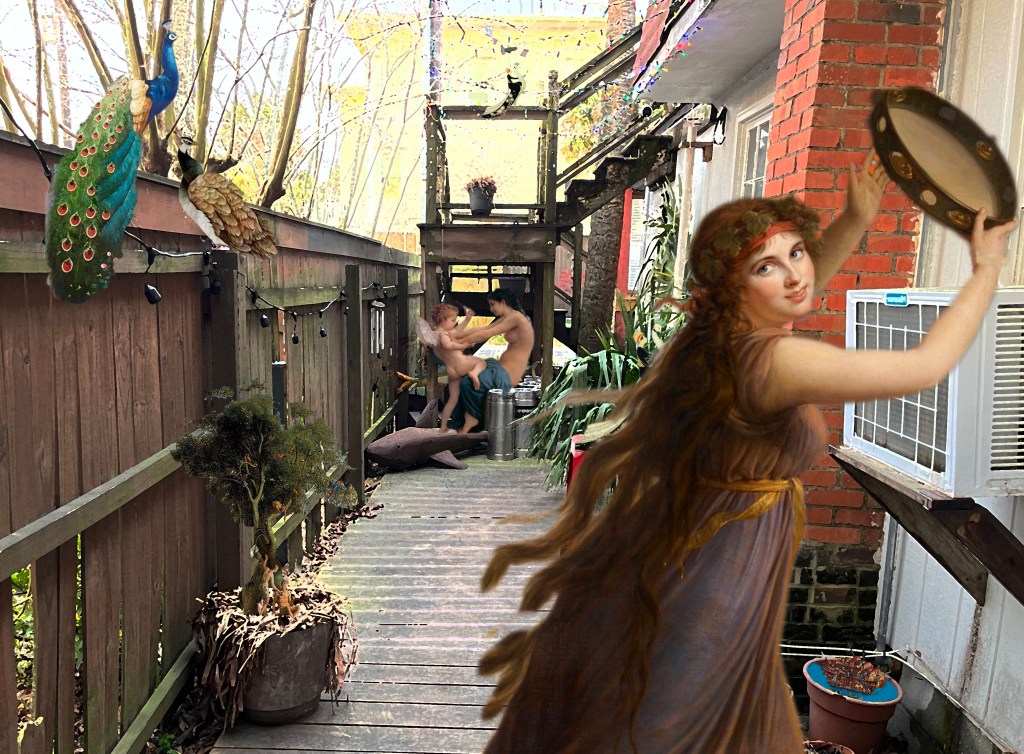

As my regular readers know, I entertain myself by creating what I facetiously call “fake paintings,” which others have described as “photo collages.” I guess that’s more accurate, or at least more precise; however, when I think of a collage, I imagine a proliferation of cutouts that create sort of visual mosaic whereas my “pieces” attempt to blend the cutouts into a dramatic scene so that the viewer isn’t aware that images have been swiped from somewhere else and inserted into the “painting.”

Here are four examples in order of their compositions from oldest to latest.[1]:

I occasionally post some of these on Facebook, and recently someone commented that AI was going to put me out of business to which I replied, “AI ain’t never listened to a Tom Waits song or changed a flat tire. It ain’t know.”

Of course, AI has probably already put traditional illustrators out of business, but to me, the visuals all look alike, smacking of early Soviet propaganda.

The same goes for AI generated prose. I can identify it fairly easily because it reads like Strunk and White on steroids with all those active verbs “clambering” to “propel” well-varied clauses that are the equivalent of the Trump Kim poster above.

It’s soulless.

Of course, AI is no doubt going to become more sophisticated, but I’d like to think it could never come up with this:

Well, it’s Ninth and Hennepin

All the doughnuts have names that sound like prostitutes

And the moon’s teeth marks are on the sky

Like a tarp thrown all over this

And the broken umbrellas like dead birds

And the steam comes out of the grill like the whole goddamn town’s ready to blow

And the bricks are all scarred with jailhouse tattoos

And everyone is behaving like dogs

And the horses are coming down Violin Road and Dutch is dead on his feet

And all the rooms they smell like diesel

And you take on the dreams of the ones who have slept here

And I’m lost in the window, and I hide in the stairway

And I hang in the curtain, and I sleep in your hat

And no one brings anything small into a bar around here

They all started out with bad directions

And the girl behind the counter has a tattooed tear

One for every year he’s away, she said

Such a crumbling beauty

Ah, there’s nothing wrong with her that a hundred dollars won’t fix

She has that razor sadness that only gets worse

With the clang and the thunder of the Southern Pacific going by

And the clock ticks out like a dripping faucet

Till you’re full of rag water and bitters and blue ruin

And you spill out over the side to anyone who will listen

And I’ve seen it all

I’ve seen it all through the yellow windows of the evening train

[1] These are printed on canvas so to the careless eye they appear to be “paintings.”

Episode 3 of “My Boys Were Back in Town, Backroads Edition Featuring Joel Chandler Harris

Episode 3 – Eatonton’s Rural Literary Legacy

[In episode 2, My ex-pat son Ned and I wended our way through backroads headed to Reynolds, formally known as Reynolds Plantation, just outside of Greensboro, Georgia, to reunite with his Aunt Becky at Uncle Dave].

Around four-thirty on Thursday, Ned and I arrived at Reynolds where we negotiated the security gate rigamarole. At the house, Becky and Dave greeted us warmly, plied us with drinks after our long (well, six hour) journey, and we did some catching up. It turns out that Becky and Dave had recently suffered a hair-raising flight from New Jersey to Atlanta, the inside of the plane perpetually rocked by turbulence for the entire time they were airborne. As she was exiting the plane, Becky found it especially disconcerting to see the pilot and copilot exchanging high fives. She informed Ned if she were going to visit him in Nuremberg, she was likely to take an ocean liner.

On Friday, Dave, who is overseeing the construction of one of the houses his son Scott is building in Reynolds, headed off to work, and Becky drove Ned and me to Eatonton so we could check out the Georgia Writer’s Museum, home of the Georgia Writer’s Hall of Fame.

Eatonton is a lovely, sleepy verdant town that reminds me of the Summerville of my youth. It seems like a pleasant place to retire, that is, if you’re not a Folly Beach hedonist hellbent on cha-cha-cha-ing yourself to death.

The museum itself, located in a coffeeshop, struck me as the literary equivalent of a science fair, consisted of tables lined up with poster board information. Eatonton and its environs have produced a remarkable number of noteworthy writers including Alice Walker, Jean Toomer of Harlem Renaissance fame, and Joel Chandler Harris, who adapted African folk tales in book form, creating the Uncle Remus stories. Milledgeville, the home of Flannery O’Connor, is a mere twenty miles south.

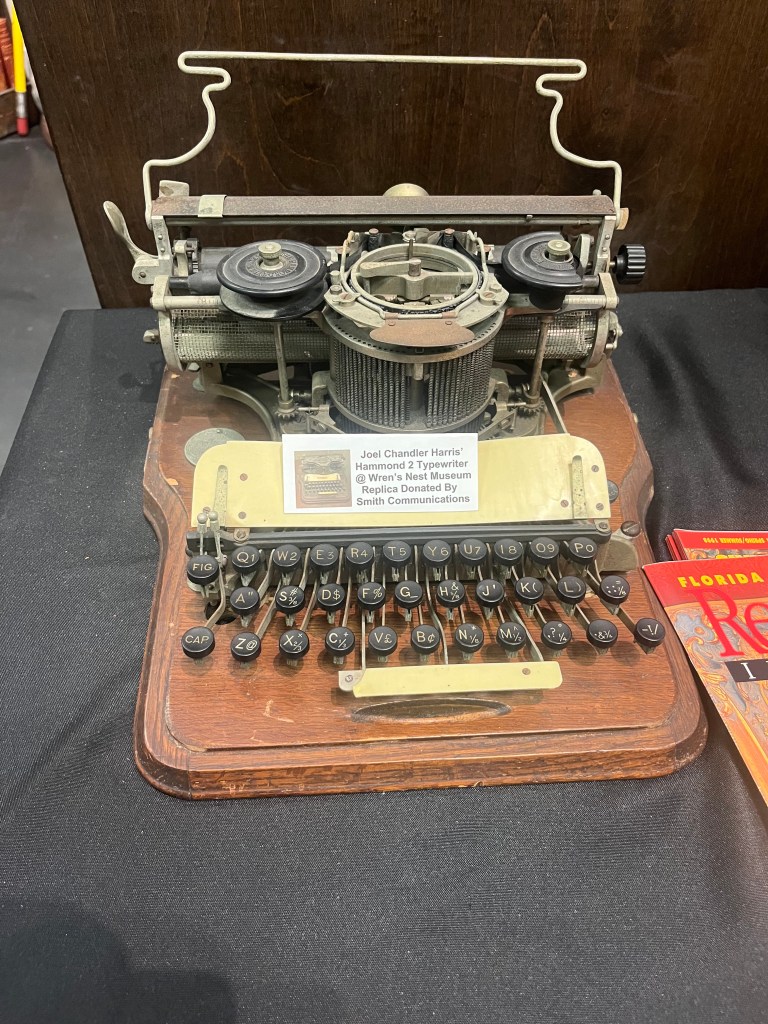

The museum houses both Joel Chandler Harris’s and Flannery O’Connor’s typewriters, plus an exhibit delineating the evolution of machines of writing, starting with primitive typewriters and ending with a progression of computers getting smaller and sleeker through the decades.

As I slowly strolled along the exhibits, The fact that Joel Chandler Harris had been born in the Barnes Inn and Tavern caught my eye. Being born in a tavern seemed odd, colorful, so I read on.

Here’s a short version of his life:

The year of his birth is uncertain, either 1845 or 1848. His mother Mary, an Irish immigrant who worked at the inn, was impregnated by a cad who abandoned his infant son and Mary. She named the baby Joel Chandler Harris after her attending physician.

Of course, illegitimacy, as it was called in my youth, was especially problematic in the antebellum South.[1] In addition to that disadvantage, Joel was redheaded and stammered, which made him a target for bullies.[2] The stigma of his “lowly” birth haunted him throughout his youth and early adulthood.

Fortunately, Dr. Andrew Reid, a prominent Eatonton physician, provided Mary and Joel with a small house behind his mansion. He also paid for Joel’s tuition (in those days public education didn’t exist in the South). Mother Mary fostered Joel’s future literary prowess by reading to him out loud, which helped him to develop the remarkable memory he would utilize in assembling the Uncle Remus tales. She read him Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield so often that he could recite lengthy passages by heart.

At fourteen, Harris dropped out of school and went to work for a newspaper, Joseph Addison Turner’s The Countrymanwith a circulation around 2,000. There Harris mastered the basics, including typesetting. Addison allowed Harris to publish his own stories and poems. Eventually, Harris moved into Turnwold Plantation, Addison’s home, located nine miles outside of Eatonton. Here Harris had access to a voluminous library and where he began devouring the classics and contemporary authors such as Dickens, Thackery, and Poe.

At Turnwold, Harris spent hundreds of hours in the slave quarters. Wikipedia claims that Harris’s “humble background as an illegitimate, red-headed son of an Irish immigrant helped foster an intimate connection with the slaves. He absorbed the stories, language, and inflections of people like Uncle George Terrell, Old Harbert, and Aunt Crissy,” who in amalgam became the narrator of the Brer Rabbit Tales, Uncle Remus.

I was unfamiliar with Harris’s biography, but what strikes me as truly remarkable is that he replicated these stories in dialect without any written sources. He essentially gave voice to and preserved these tales that had been stored in the brains of Africans, transported across the Atlantic in slave ships, and told and retold in slave cabins throughout dark nights of captivity.

Because of the Disney movie, Song of the South, Harris has been tarred (pun intended) as being a racist, which is unfortunate. What Harris did was preserve a rich trove of folklore featuring an African trickster who used his wiles to outfox foxes, tales where the underdog prevails. Of course, you can accuse Harris of cultural appropriation, but to my mind, the dialect enriches the tales, making them much more linguistically interesting.

After the war, Harris moved up in the world of journalism, working at the Atlanta Constitution for nearly a quarter century, and addition to the Remus tales, he published novels, short stories, and humorous pieces. Luminaries such as Theodore Roosevelt and Mark Twain were among his admirers. Alas, he was an alcoholic, and died from complications from cirrhosis of the liver at 59.

After our visit to the museum, Becky gave us a driving tour of the area, which includes a dilapidated chapel where Alice Walker’s ancestors are buried. We arrived back at Reynolds in the early afternoon, looking forward to Cousin Scott’s arrival the next day. At the museum, Ned had bought me Jean Toomer’s Cane, a literary mosaic of poems and short stories that brings to life a subculture, which reminds me of my work-in-progress Long Ago Last Summer, an up close and personal exploration of real life Sothern Gothic.

In short, it was a very meaningful morning and afternoon for Ned and me.

Alice Walker’s Childhood Home around 1910

[1] Of course, “bastard” was the preferred 19th Century nomenclature.

[2] As a former redhead, I can emphasize. If interested, check this LINK out.

My Boys Are Back in Town, Episode 2: Blind Willie’s Gravesite

EPISODE 1 of “My Boys Are Back in Town: Joel Chandler Harris Backroads Edition” ended with my son Ned, who lives in Germany, and I-and-I embarking on a backroads trip to northern Georgia. It was Ned’s idea to see his mother’s sister Becky and her husband Dave during Ned’s two weeks in the States, and I volunteered to come along. My sister-in-law Becky is a Birdsong, and growing up, my boys were much closer to the Birdsongs than the Moores. The Birdsongs resembled the Brady Bunch, a prosperous blended family of non-smokers and non-alcoholics/drug addicts. The Moores, on the other hand, more or less resembled a mashup of the Addams Family and Tennessee Williams. For example, Becky had never vomited on Ned in a station wagon after picking her up from a halfway house to celebrate Christmas in dysfunctional Snopesville. Alas, the same can’t be said of his chain-smoking bipolar Aunt Virginia.

As a bonus, when Becky and Dave’s son Scott heard we were coming, he decided to drive over from Atlanta to share the weekend with us.

With my bonus daughter Brooks in school, she and my wife Caroline couldn’t make the trip. Caroline, cognizant of Ned and my spaciness, made sure were had packed the essentials – tangles of electronic chargers, sufficient socks and underwear, gifts for the hosts, and a cooler of various malted beverages.

We took off on Thursday morning around ten, but there was a problem: when I punched Google maps, my phone informed me that I was not connected to the internet. Since Ned’s German phone was dataless, we turned around and retraced the block or two we had traveled on Hudson Avenue, Folly Beach, SC. I climbed the stairs to my wifi-rich drafty garret to troubleshoot. No sooner than I had fired up the iMac, Ned called from below, “It’s ATT, dad. ATT’s down.” So I retrieved a venerable relic of a roadmap, and we were off.

Caroline and I had made this trip a couple of years earlier when I had introduced her to Becky and Dave, so I was somewhat familiar with the first leg of that took us to the fringes of Walterboro. On the previous trip, Caroline and I had made a pilgrimage to Blind Willie McTell’s grave outside of Thomson, Georgia, and headed back towards the Savannah River, Caroline caught sight of a truly weird roadside attraction, a junkyard turned art installation that included a crashed helicopter and a sexy mannikin in a telephone booth[1]. Ned was eager to see it in person and share it with his friend Claudia, who is a prominent German artist.

This is what had caught Caroline’s eye

We headed down 17 South and stopped in the Red Top community to fill Caroline’s Prius with the cheapest gas in South Carolina. We were about a mile or so from Ned’s first childhood home in Rantowles, so we made a brief detour, noted the changes (or at least I did; Ned was yet not walking when we moved to the Isle of Palms). I noticed that the shrubs Judy and I had planted were still going strong, had, in fact, outlived her. Her ghost accompanied us throughout the trip, a pleasant though somewhat melancholy companion.

At Jacksonboro, right past the now defunct Edisto Motel Restaurant, which had in the day conjured the best fried seafood I’ve ever eaten, we took highway 64 West towards the heart of murderous Murdaugh country, Colleton County. That’s where we discovered that ATT was back, and we need no longer rely on yesteryear’s technology to get us to Allendale, before we crossed the Savannah River into Georgia.

Allendale is a lovely word, harkens back to Merry Old England, Robinhood and all that jazz, but the city nowadays is a decaying corpselike town of abandoned motels, convenience stores, and restaurants.[2] Ned has perhaps inherited from the Moore side of his genetic heritage a morbid sensibility. Rather than getting the hell out of there, we tooled slowly, taking it all in, taking what used to be called photographs.

We decided to visit Blind Willie’s grave on this trip, and the art installation on the way back, since we had left late because of the ATT snafu.

The grave is located in the yard of a small, red-bricked Baptist Church outside of Thomson. By the way, not only was Blind Willie a great bluesman, but he’s also the eponymous source of one of Dylan’s underappreciated masterpieces.

Here’s a snippet from “Blind Willie McTell”:

See them big plantations burning

Hear the cracking of the whips

Smell that sweet magnolia blooming

See the ghosts of slavery ships

I can hear them tribes a moaning

Hear that undertaker’s bell

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

Ned and stood by the grave, Ned tossed some German Euros on the slab, and with that mission accomplished, we made our way to Becky and Dave’s.[3]

In the next episode, Becky introduces us to the Georgia Writer’s Hall of Fame in Eatonton where I learn some stuff and Ned buys me a book after I buy Becky a book.

Now that’s what I call a “cliffhanger” or maybe a “coat hanger.”

Here’s Dylan himself singing the above-quoted verse:

[1] Here’s a LINK if interested.

[2] It makes the Trenchtown of the Jimmy Cliff’s The Harder They Fall look like Beverly Hills. It’s the opposite of Reynolds, where Becky and Dave live, a picturesque golf community of rolling hills and million dollar houses on and adjacent to Lake Oconee.

[3] Note to those who read episode 1. No, we didn’t pick up a blind hitchhiker, complete with red-tipped white cane. Never trust a teaser.

My Boys Are Back in Town: Joel Chandler Harris Backroads Edition

On the main drag through Allendale, SC.

Episode 1

Family Time

My far flung sons, Harrison up in Chevy Chase. and Ned over in Nuremburg, came for a visit in mid-February. It’s rare to be together in one place; however, Ned decided to come down for two-plus weeks during an academic break, and Harry took a couple of days off to join Caroline, Brooks, and me with his wife Taryn and their boy, Julian Levi Moore, the mighty mini-mensch, my grandson.

Harry and Taryn rented a bright yellow cottage around the corner, something you might encounter in a Winslow Homer watercolor, one of the many spiffed-up two-bedroom houses on Folly that in rental brochures affect a Key West vibe.

Julian, who is two-and-a-half, is as verbal – as his late grandma Judy would say – “as all get out.” Though he conflated our house with the state of South Carolina, and would say when he was in the rental, “I wanna go to South Carolina, I wanna go to South Carolina.” [1]

the mighty mini-mensch

We all had a great time, and the boys and I got to hang in a bar reminiscing about days of yore – surfing on the Isle of Palms, playing wiffle ball in our backyard, bedtime readings, and movies in theaters we’d seen together, starting off with Snow White and ending up with David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive.

Harrison (left) and Ned at Lowlife

We also got to celebrate Brooks’ 15th birthday, a festive occasion for sure!

Brooks

But, alas, Harrison had to get back to work, so we sad our sad goodbyes, sad for me anyway, because of the limited number of these encounters left as my twilight continues its necessary progression.

[Hello, sorry to interrupt, but I’m Marcus Aurelius, and I do not approve of that previous paragraph.]

You’re right, Marcus, that sounded whiny. And, sure, we can FaceTime. It’s not like when we depended on handwritten letters for communication. I remember my uncle Jerry’s infrequent missives to my grandmother when he was in the service. That had to be tough.

Uncle Jerry (standing) at my grandparents’ service station in Summerville

Back Roads Road Trip

Abandoning Caroline and bonus daughter Brooks, Ned and I took off to see his Aunt Becky, Uncle Dave, and Cousin Scott in Reynolds, nee Reynolds Plantation, a golfing development on Lake Oconee between Greensboro and Eatonton, Georgia.

I almost always go on the back roads because you don’t see shit like this on the Interstate.

Or curiosities like this.

We had a problem, though. ATT had crashed, Ned’s German phone was dataless, so [gasp], we’d have to negotiate the labyrinthian lefts and rights, rights and lefts, four way stop signs on Highways 17 South, 64 West, etc. etc. with an anachronistic road map, a document incapable of saying out loud in a soothing yet robotic tone, “At the light, take a right, Stonewall’s Calvary Road.”

How does the trip go? Do we pick up a blind hitchhiker complete with red tipped white cane?

Find out next time to Episode 2, “Allendale Ain’t Looking So Good, Though Come to Think of it, Neither Am I.”

[1] When hearing our waitress Jaime at Jack of Cups Saloon list food kids might like, before she was finished, he looked her in the eye, and said, “Grilled cheese please.”