This is the beginning of my current work in progress entitled Long Ago Last Summer. The first draft is completed, so now comes the painstaking work of refinement. What’s below are the first paragraphs of the 7100-word first chapter.

Chapter 1

Those Who Think, Those Who Feel

1

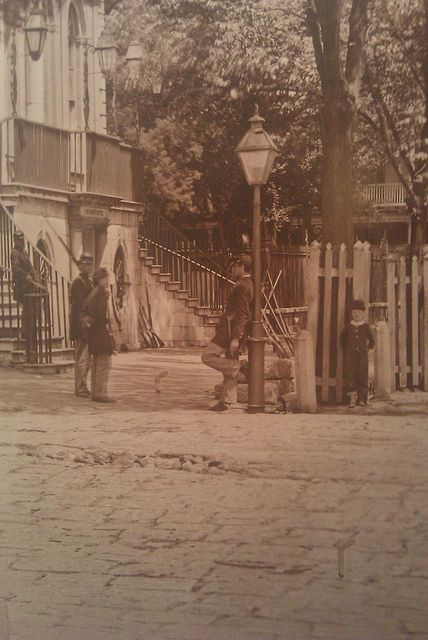

My father aspired at some point early in his life to become a tragic figure, but unfortunately, even at that, he failed. Born in the 1920s in the shabby outer edges of Reconstruction’s long shadow, he grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, in those days a rundown museum of a city with its weather-beaten mansions and black women calling out in Gullah, balancing baskets of vegetables or laundry on their heads. A talented storyteller, my father was a virtuoso on the heartstrings, recounting unfortunate events from his melancholy childhood, an exotic world of paregoric addicts, ancient cotton-haired slave-born coloreds[1], blind street musicians, and blue-blooded eccentrics. I can conjure his depiction of himself even now, a ragamuffin Depression boy in knickers and cap hawking newspapers on city street corners. It’s odd that I picture his old stories in black-and-white. Perhaps it’s because of the photographs or the old movies of that era. Memory is a curious thing. I guess you could say it’s a collection. The older we get the more we discard, up to a certain point. My father, however, was a curator with a very narrow thematic interest. And what he kept was very well preserved and artfully presented.

2

My father felt unloved by his father, a distant presence puffing a pipe, turning a page of The Saturday Evening Post. I remember meeting my grandfather only once or twice when my father was alive, and I never heard my father utter a kind word about “the old man.” In my post-mortem meetings with Grandfather Postell, he was what you might call lively but egocentric. He’d talk about his golf and his dead Airedales and about his photography but never expressed any curiosity about what was going on in my little life. He had been the youngest of five, the only boy, the son of an Upcountry state senator, and perhaps spoiled by the plump quartet of his elder sisters, my great aunts, formidable eccentrics in their own rights. I can very well imagine not being loved by this man, though, on the other hand, I can’t really imagine being abused by him.

His son, my father, absolutely worshipped his own mother, whose portrait hung, eerie and Oedipal, over my parents’ four-poster bed. She was beautiful and angelic and elegant and the brains behind the studio. Grandmother Postell’s death from T.B., three years before my birth, was right out of “Ligeia.” Yellowed photographs of her propped up on pillows in a ghostly white gown survive in black picture albums. As a little boy, I remember carefully turning the pages of those albums, gazing at my tall slender grandmother leaning against an antique car, my father half-her-size, standing beside her with his thick wavy hair combed straight back.

As a child, listening to my father’s version of his own childhood, my eyes would sometimes fill with tears as he would in his gruff way catalogue his sorrows. He made me feel lucky to be me, and I felt guilty because I took for granted the bright sunshine of Suburban Summerville, my middle-class neighbors, and the leisurely hours I had to loll away shooting marbles or riding my bike on lazy Saturday afternoons. Unlike his own father, my father had sacrificed everything for us by working at the dreary Naval Yard, a job well below the significant talents he possessed. My father saw himself as a marked man, doomed to a life of bad luck, and I guess you could say that in some ways he was.

Though, by Depression standards, at least economically, my father didn’t have it all that bad. He lived with his parents, who had been employed as portrait photographers but who had lost everything in the Crash. During the Thirties, they stayed with his mother’s parents who lived in the second story over a pharmacy they owned on the corner of Spring Street and Ashley Avenue. Anyone who owned a business that didn’t fold during the Great Depression shouldn’t complain too much about deprivation. With money so scare, being a child laborer[2], especially a paperboy, might be considered a blessing, but not to my father, who viewed himself as Oliver Twist, a figure to be pitied, and perhaps he deserved that pity. I wasn’t there to witness his life.

His stories, though, always accentuated the poverty. I’ll grant that living with eight other people in 1200-square feet isn’t enviable, but it’s not exactly The Grapes of Wrath either. After all, deprivation was pretty much the way-it-was in Charleston during the Depression, a city isolated and traumatized by the events of a war that still could claim a few living veterans shuffling down its sidewalks. Nevertheless, I don’t dispute that something must have been lacking in his childhood, and I suppose that the best guess for what was lacking is love. My own mother, in the unenviable position of following a dead saint, once surmised that what had ultimately been lacking in Daddy’s life was maternal love, not so much as paternal love, but Daddy would never have owned up to that. An insinuation like that would have thrown him into a rage, and he was the furniture-smashing type when he lost his temper.

When not working or getting expelled from a series of schools, my father roamed the streets of the Upper Peninsula. Here, he could put his seemingly endless store of anger to good use, saving a squirt from a cowardly bully or bloodying the nose an arrogant Northerner who had indiscreetly commented on the corporeal charms of some perceived paragon of Southern ladyhood. In the stories my father told us, he was always the cavalier, the heroic fellow, always smaller than the oppressors he pummeled, always a figure of sympathy. Boxing was the only sport he cared anything about. I can remember his yelling at the television on Friday nights, barking advice to Sugar Ray Robinson or Archie Moore, “Keep that left up, keep that left up.”

Of course, to be a tragic hero you’re supposed to be somewhat bigger than life and somehow bring your calamity down upon yourself, perhaps because you suffer from a fatal flaw, like too much ambition or too much pride, or in my father’s case, too much a flair for the dramatic. Nevertheless, his story, which is also my story, doesn’t quite make the grade as far as tragedy is concerned. I personally see our lives as a dark comedy, more Beckett than Tennessee Williams. You may have heard the saying, “Life is a comedy to those who think, but a tragedy to those who feel.” Like everything else, it all depends upon your perspective.

[1] The polite word in those days.

[2] Child laborer was the Dickensian term my father used to describe his employment with The News and Courier.

Looking forward to reading more. I feel like I understand your dad…

And your mom seems kind and empathetic…mom’s are important like that.

D. Bennett